Sweet mother

Reading Time: 5 minutes

This song is an African anthem from the highlife era of the 1970s. It is a tune that speaks of the love, gratitude, appreciation and admiration that most children reserve for their mothers. It celebrates the universal bond between mother and child. In that spirit, I would like to tell you about two special mothers and how the vision, sacrifice and hard work of one brought me to the other

Sweet Mother.

This song is an African anthem from the highlife era of the 1970s. It is a tune that speaks of the love, gratitude, appreciation and admiration that most children reserve for their mothers. It celebrates the universal bond between mother and child. In that spirit, I would like to tell you about two special mothers and how the vision, sacrifice and hard work of one brought me to the other.

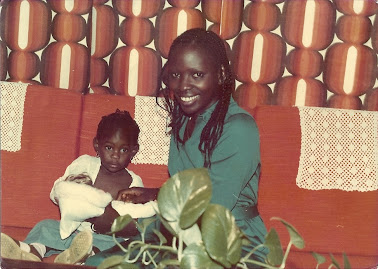

The first story is about my own mother, Jamilah. She came of age on a continent that was at the very beginning stages of independence, when many new African nations were thrust into the mainstream and expected to thrive. Like many girls even today, she was not sent to school. Her parents did not fully grasp how the world was changing around them and how an education could equip her to negotiate life.

Instead, she was married off at 13, a child, and sent to live hundreds of miles away from all things familiar. How is a 13-year-old expected to cope, let alone thrive, when she can’t read or write, speak the local language or doesn’t have any marketable skills? She copes by relying on her husband. And for a while, that’s what she had to do. Having just had her first child at fifteen, she was insulated by the fact that my father was there, that he worked and could provide for the family. A very tenuous and vulnerable position, wherein your livelihood is completely dependent on the fortunes and magnanimity of another person, even if that person is a husband. What would you do in the event of illness, job loss or death?

So it came to be that while most girls her age were planning on what dresses to wear to prom, my mother was compelled by the circumstances in her life to start planning a future for her children. She tells me that from the very beginning, she did not know exactly how she would accomplish it, but her aim was very clear: to radically change the direction of her children’s lives, especially for her daughters. She felt the necessary step in this process would be to ensure we got a good education. What she did next, I believe, definitively altered our collective destinies.

She enrolled herself in night school to learn how to read and write solely because she wanted to be able to help us with our homework. For the first part of my life, I remember my mom sending us off to school in the morning and leaving for school herself in the evening after giving us our baths and feeding us dinner. She taught me math before first grade.

When I was just eight, we had to flee a civil war and relocate to Guinea. During that time, we had each other but we lost everything else. The company my father worked for shut down and he lost all sources of income, property and savings to the war. The responsibility for financially caring for our family eventually fell to my mother. Without missing a beat, she rose to the occasion.

She secured loans from family members and launched her first business selling baby clothes by the roadside in the town where we lived. Over time, she grew that business and continued to pour everything she had, financial and social capital, into ensuring we had access to a good education. My mother’s determination to educate herself and to create opportunities for us, despite cultural barriers and difficult circumstances, created an ideal and planted a seed of hope that allowed me to be fearless in pursuing my own dreams. Today, I am a lawyer who just landed her dream gig at BRAC USA, a support organization of BRAC, which is a leader in creating opportunities for people to end poverty for themselves and create change in their communities. As a member of the targeting the ultra poor program (TUP) global advocacy team, my work focuses primarily on women living in ultra poverty – those living on, roughly, sixty cents or less a day.

It’s been a long while since my mother moved to the US, started a thriving business and created a secure life for us. Imagine my surprise when on a trip to rural Bangladesh I found someone who’s story mirrored her own.

It turns out my mother’s story remains a universal one, even to this day.

Deep in northern Bangladesh I met the most vibrant woman, who reminded me so much of my mother that I immediately wanted to hug her. She too had been married off at a young age, she too was raising children in seemingly impossible circumstances. Before 2011, Shamsunnahar was living in severe poverty. She had lost her husband and could not afford to feed herself or her children, so she sent her daughter away to live with relatives, where her daughter had to drop out of school.

Thankfully, even though Shamsunnahar was very poor, she still had a home. Her husband, on his deathbed, made his family promise not to kick her out when he died.

In 2011, Shamsunnahar was enrolled into the BRAC TUP program, a combination of carefully sequenced interventions that address the specific and varied needs of the poorest, known as the ultra poor, most of whom are women. The program provides women with the support that they need to give their families a chance to build a better and more economically stable life. In the program, Shamsunnahar received basic assets, livelihood training and health support. She was soon able to bring her daughter back home and enroll her in the local BRAC school. She graduated from the program in 2012 and has since purchased land on which she cultivates eucalyptus, papaya,

She graciously welcomed me and the BRAC team into her home and shared with me her life story. She lives in a wide and airy yard with her two children, a girl named Shaquila, 14, and a boy named Shaquib, 12. There is a certain air about her, an efficiency to her mannerisms, a certain warmth in the way she regards other people. As she entertained us and answered our questions, she was simultaneously using her sewing machine and doing other chores around her home. These days she is a very busy woman – a farmer, a seamstress and an entrepreneur. I instantly recognized her tempo. Her drive to accomplish the tasks that provide for her family and secure their future is one that I’m intimately familiar with.

Shamsunnahar says she works from dawn to dusk to ensure that she never goes back to how things were, to her children going hungry. “My dream is to educate both my children well so that that they will be able to get jobs and have bright futures,” she says. “To fulfill this dream, though it is difficult to work alone 12 hours a day, I do not mind. In fact, I enjoy it because I am doing it so that my children may have a good future.”

I have no doubt in my mind that she will accomplish her goals. All that women like Shamsunnahar need is a little boost, a fighting chance to change their lives and the lives of their children. I know this because I recognized my mother in Shamsunnahar . They are of a different generation, time and place, but faced with similar circumstances. Their instincts are the same: envision a better future for their families and work hard to make it possible. Shamsunnahar children are happy, healthy and in school.

My mother did many more things for me and my siblings that are impossible to capture in one blog post, but the message here is that like Shamsunnahar, my mother’s living legacy to her family and children is a deliberate and consistent choice of sacrifice over self, enterprise over pity, hope over despair, and hard work in crisis.

I am doing exactly what I dreamed of doing with my life, and my mother is primarily responsible for that. She dreamed for me when I could not and invested in that dream. For that I am eternally grateful. Sweet Mother, indeed.

Happy Mother’s day to Shamsunnahar, Jamilah and all mothers around the world who consistently give us their best.

Make a donation to BRAC to support mothers around the world.

Aïssatou Diallo is a program associate at BRAC USA and a part of the TUP global advocacy team.