Mobile money can be scary. How can we change that?

Reading Time: 3 minutes

Mobile money has shown immense potential over the last decade, but remains a source of dread for many people living in poverty and inequality, particularly women. How can initiatives be designed to gain their trust?

Selina Akhter*, the eldest of five sisters, is an aspiring entrepreneur from Habiganj in Sylhet, northern Bangladesh. Her husband is a migrant worker abroad. She is confident and determined to provide for her family, but does not use mobile money as a vehicle for saving, for the same reasons as many other women – primarily, poor digital literacy and socio-cultural constraints.

Selina invests in livestock and poultry. She works hard to save and make a living.

“I dream of my own farm. My husband loves the idea. I have to keep it a secret from my in-laws, though. They don’t want me to work.”

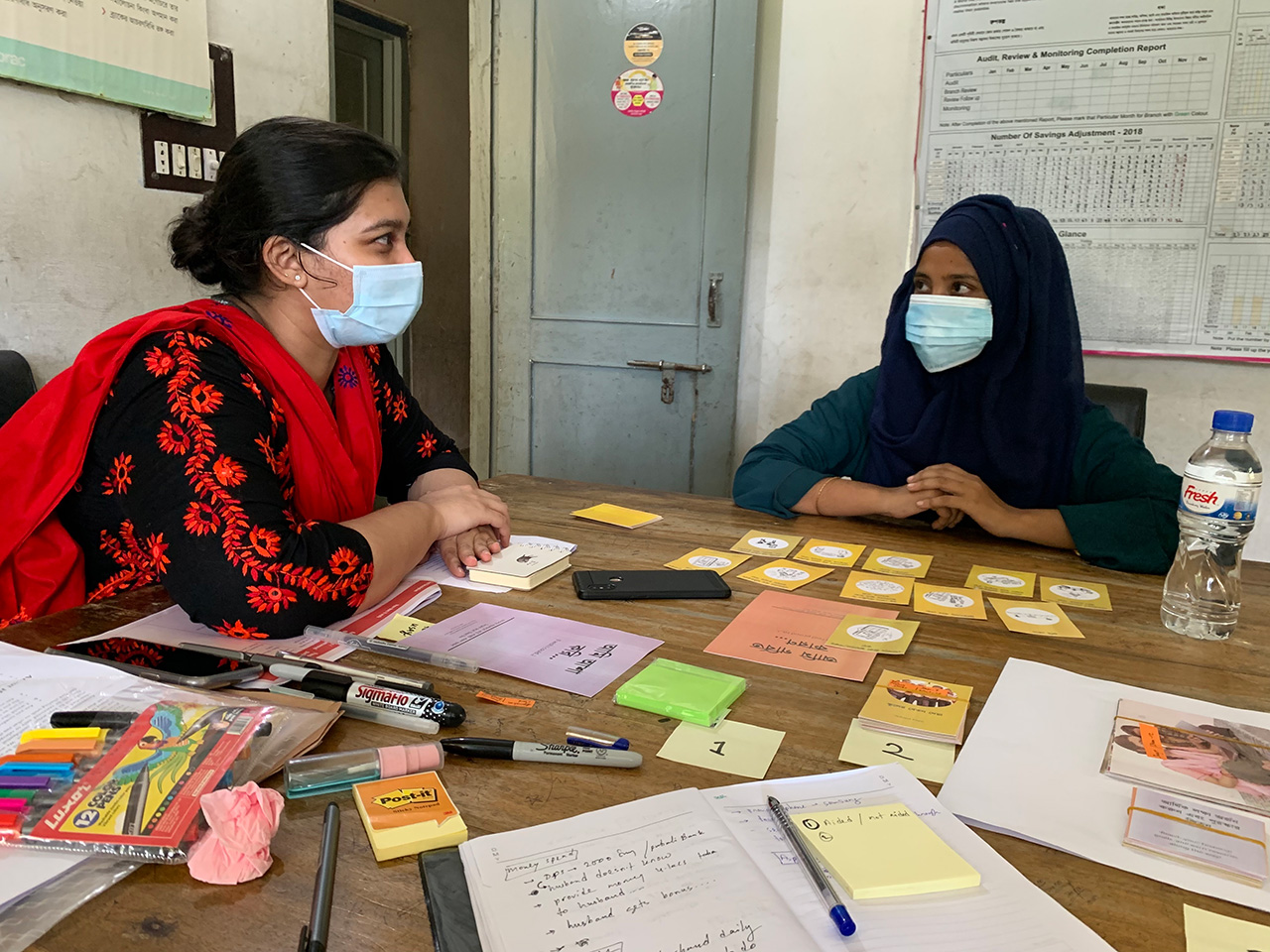

Selina sharing her future plans during a card-sorting exercise as part of Shakti micro-pilot design, Bangladesh. Photo credit: © BRAC

BRAC’s Shakti micro-pilot project provides incentives for women like Selina to get familiar with digital financial services, by fulfilling repeated savings targets in groups. Here is what we have learned about working with women like her through the project:

Personal savings give women financial control, and mobile money makes that easier

While individual experiences vary greatly, women have less control over household finances than men. This is often because of the so-called ‘kin tax’ – where women are forced to contribute their income for their family or business, even if they want to do something else, like save.

Savings accounts which protect women’s privacy via mobile phones give women like Selina power over their financial futures.

What does Selina need?

Services close to her home, a motivating and safe environment to seek guidance and help from, and the opportunity to gain her family’s validation of her work.

Selina makes four cash-ins over eight weeks and completes worksheets guided by a group leader. The worksheets facilitate Selina’s livelihood planning and augments her knowledge on digital financial safety. Every time Selina cashes in, she gets a cash reward – that increases with additional cash-in she makes.

Female participants placing stickers on their tracking booklets during the micro-pilot’s sign-up meeting, Baniachong, Sylhet, Bangladesh. Photo credit: © BRAC

Creating a framework to support Selina

Who/what is her biggest barrier? Selina had used mobile money wallets, but she had an underlying fear of losing her money. The stakes are high, so she avoided digital platforms for savings. Unsupportive in-laws did not make the situation any better.

Who/what is her biggest enabler? She is surrounded by other people who motivate her. With help from a cousin, she researched smartphones and eventually saved enough money to buy one. Her uncle gives her new ideas and helps her explore new mobile wallet features.

Her motivation? She has a thirst for knowledge and a desire to be her family’s financial backbone. She is also working to support her sister, and eventually plans to live with her husband in Saudi Arabia.

“I don’t know why my mother-in-law is angry with me. But if I get a business started, who will tell me to stop?”

Women receiving certificates for completing BRAC Shakti micro-pilot programme in Kagapasha, Hobiganj, Bangladesh. Photo credit: Raiya Kishwar Ashraf © BRAC

The last time we spoke to Selina, she expressed her desire to buy two cows. When we visited again, she had four.

What were the results from the micro-pilot and what do they mean in practice?

All 40 women in the micro-pilot completed the programme, with 75% of groups choosing the higher savings target of BDT 500 (USD 6) per week. When asked how they spent their reward money, they said they bought something for the home, had a small picnic, and, interestingly, even invested in ducklings. In terms of learning, they frequently checked their account balances and waited for payment confirmation SMSs, which showed an increased understanding in using the tool.

There was no long-term change in regular cash-ins or balance maintenance, however. For us, this meant that the next step will be promoting adoption at local markets and other places Selina frequently visits.

Communication and transportation in the haor (wetlands) areas are complex and expensive. Photo credit: Sumon Yusuf © BRAC

The project is now being piloted with 5,000 women from across the haor (wetlands) region in northeastern Bangladesh, where communities are geographically and economically isolated from traditional services. The pilot will investigate what motivates women to save digitally, and whether group-based learning can enhance their confidence in digital financial services.

*Name changed to protect anonymity

Maleha Chowdhury was an Innovation Associate at BRAC Social Innovation Lab. Raiya Kishwar Ashraf is the Innovation Ecosystem and Partnerships Manager at BRAC Social Innovation Lab.

Cover photo: Emdadul Islam Bitu © BRAC

Social Innovation Lab is a knowledge and experimentation hub at BRAC, the world’s largest non-government organisation. We test, prototype and support scaling new ideas to solve the most complex social problems, to support BRAC by capitalising on emerging opportunities and catalysing innovation throughout the organisation. Learn more: https://innovation.brac.net/