Reading Time: 3 minutes

In 2016, TB claimed the lives of 1.3 million people across the world. Four million cases of TB have been undocumented or not reported. One of the bizarre features of TB is that it remains inactive, producing no symptoms, for long periods of time.

An epidemic might be on the rise. Two of the world’s most lethal infectious diseases are mostly being overlooked in the makeshift settlements of Cox’s Bazar, demanding immediate attention to prevent any possible outbreaks in the future.

After nine months since the crisis rapidly unfolded, more people are coming out with the symptoms of cough and uncontrolled fever. Well-coordinated teams of health workers are working round the clock to ensure that these numbers do not rise any further.

Shahina Akhter visits at least 40 homes a day, working tirelessly under the intense humidity of tarpaulin roofs and bamboo walls. She is one of the foot soldiers for communicable disease control within the camps. Shahina works tirelessly, looking out for symptoms of TB and Malaria; asking every member of the household, and documenting their information in a register book.

©Human Crescent

When she finds a person exhibiting symptoms, she uses a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) to detect malaria. The test comes in a small kit packed with gloves, regents and a device. In some cases she prepares a blood slide to be examined at the nearest laboratory. There are times when a household member experiences continuous coughing for two weeks with or without other symptoms of TB. Shahina then provides a small pot for them to collect their sputum early in the morning. During her visit the very next day, she collects sputum for the second time in a different pot. She submits all the samples to the nearest laboratory by afternoon.

Why are these diseases catching global attention?

In 2016, TB claimed the lives of 1.3 million people across the world. Four million cases of TB have been undocumented or not reported. One of the bizarre features of TB is that it remains inactive, producing no symptoms, for long periods of time.

The 21st century has witnessed an upsurge of mass migration, including displaced populations escaping from turmoil and disasters. UNHCR has reported that 85% of these cases have arrived from countries already highly burdened with TB- where more than 200 new cases emerge from every 100,000 people.

Such is the case in the far reaches of Cox’s Bazar and Bandarban, adding to the pressure of more TB cases being “missed” from the system. Additionally, the upcoming monsoon season is suspected to bring with it a mass of mosquitoes, massively increasing the chance of a malaria outbreak in one of the world’s largest humanitarian crises.

Community health workers making door-to-door visits in Kutupalong, Cox’s Bazar. ©BRAC/Kamrul Hasan

The National Response Plan

Bangladesh is one of the prime model examples of community mobilisation for disease control, especially for TB and malaria. The success was due to the collaboration between the government and its partners. The main agenda of this circle of health experts is to diagnose early and treat promptly, with their patients as the main focus. This prototype was easily replicated, and established in the makeshift settlements of Cox’s Bazar and Bandarban.

The control pattern begins with community health workers visiting door-to-door at daybreak- identifying suspected cases of TB and malaria, TB cases (people confirmed with the disease back in their village, but with documentation lost) and close contacts of TB. Once identified, samples are taken and sent to the nearest laboratory for tests. Immediate treatment is provided by the health worker once a malaria case is diagnosed. In terms of TB, diagnosed cases are registered, and patients are provided with regularly supervised treatment by an adjoining community DOT (directly observed treatment) provider. This person is usually a family member, their neighbour who fled from Myanmar together, or a Majhi (community leader). The health worker regularly checks the performance of such DOT providers, ensuring treatment adherence.

Health workers have conducted nearly 39,000 microscopic tests for TB, 11,280 RDT and 30,000 blood slide examinations for malaria in the last nine months since September 2017. The programme was successful in identifying nine cases of malaria and over 1,000 cases of TB.

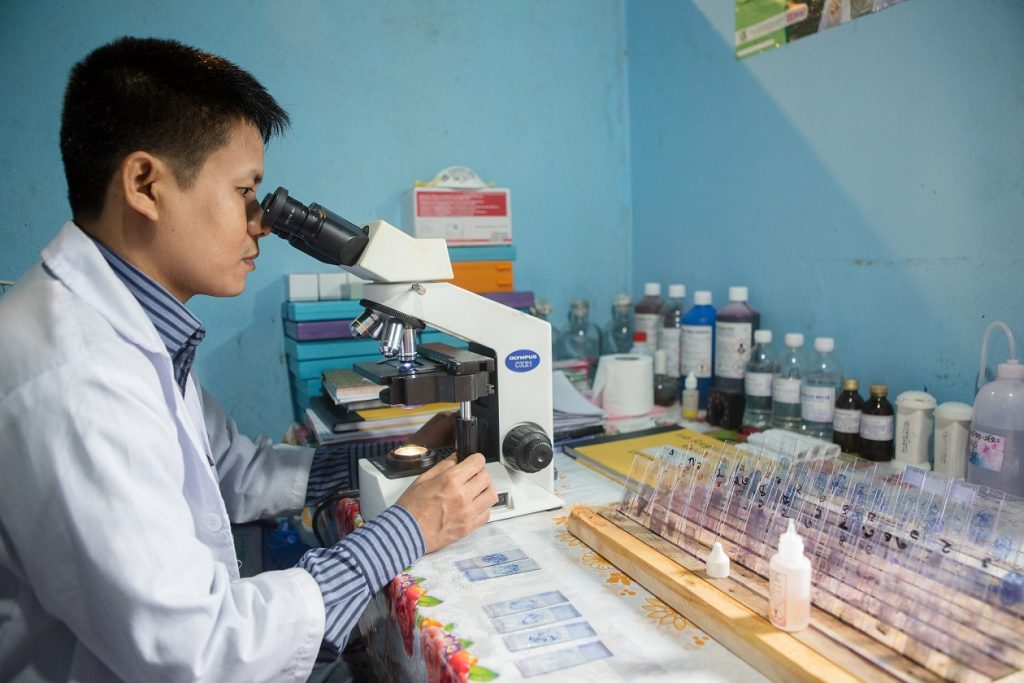

Establishing more laboratories- the backbone of detecting TB and malaria- inside most primary health centres and clinics is a crucial step towards extensive coverage. ©BRAC/Kamrul Hasan

The next frontier: Technology to combat TB and malaria

To boost the current model, mobile units packed with a digital X-ray and molecular assessment tools called GeneXpert are to be established for quicker detection of TB cases. The National response has partnered with numerous agencies that have mobile health clinics to refer more cases to laboratories and start early treatment. Establishing more laboratories- the backbone of detecting TB and malaria- inside most primary health centres and clinics is a crucial step towards extensive coverage. This will allow health workers to reach every household in every remote corner of every camp.

Farhan Patwary is a medical officer of BRAC’s communicable disease programme and TB control.