Tackling the climate crisis – with a flower: A farmer’s diary

Reading Time: 4 minutes

Extreme soil salinity is rendering thousands of hectares of farmland in coastal Bangladesh barren for months of every year. This slow-onset impact of the climate crisis is forcing millions of farmers to abandon a centuries-old – and one of the most basic – livelihoods. But not all is lost. Ashim Shikari is a farmer adapting to the climate crisis through sunflowers.

We have a new name for salt. We call it fire dust.

Why? Let me tell you.

I farm and live by the coast in Patuakhali, in a remote corner of southwest Bangladesh. Here, we used to have all six seasons, and they would play out the same, year after year, in all their glory – Grishmo (Summer), Borsha (Monsoon), Shorod (Autumn), Hemonto (Late Autumn), Sheet (Winter) and Boshonto (Spring).

Now we have just three seasons – a summer that sucks the life out of the land, a monsoon that brings punishing cyclones and floods and a dry winter that kills everything – even mung beans – the hardiest of crops.

Then there is salt, the taste we all loved – but have grown to hate – which is here for all the seasons now. It comes in with extreme tides, with cyclones, with floods – an unwelcome visitor who never leaves.

Ashim with his sunflower field. © BRAC 2023

Cyclones torment our lives for just a couple of days, but what people who don’t live with them don’t see is that they leave behind this salt brine on our fields. That stagnant, salty water stays for months. When it eventually evaporates, or seeps into the ground, it leaves a layer of flaky white salt that covers the whole ground like a tattered white bed-sheet.

Nothing grows on salt – and I know nothing other than growing crops.

We call it – salt – fire dust, because it burns the soil like fire.

When I tried planting rice in this salty soil, my rice shoots turned yellow and dried up. I tried my luck with watermelons, but they’re thirsty, and irrigation costs a lot of money – BDT 3,300 taka (USD 30) per acre, to be exact.

I hear people call my situation ‘the climate crisis’. Who created this crisis – and why am I having to pay for it? These thoughts circle over and over my head. It would have been okay if thoughts satisfied hunger – but they don’t, so I return to my fields, day in and day out, trying to grow new things, trying to keep food on the table.

Smiling sunflowers

I remember the first time I heard about farming sunflowers. I had a lot of questions. What do I do with them? How do I process the seeds? And, most importantly, how will they grow in this salty soil?

The first type of sunflower I tried was Hysun 33, a salt-tolerant variety. I took training on how to manage it and planted it in my fields. I gave it my everything, like I do for every crop. I was extra excited this time though.

And grow they did! I had never seen any crop grow so vigorously in our salty fields. The seedlings looked so healthy it was like they were made for a diet of fire dust.

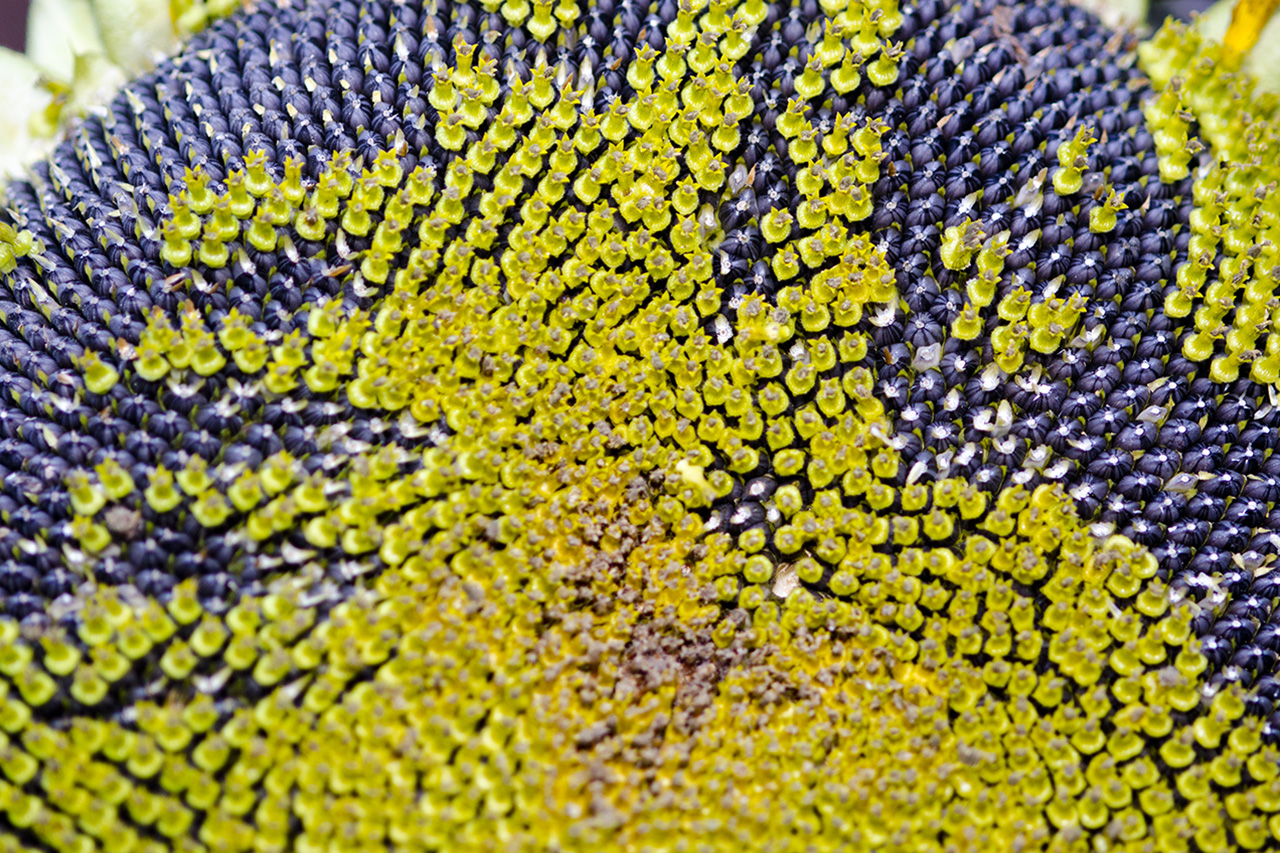

Soon the blossoms started. I crossed my fingers every morning when I went to the fields. I was hoping for one flower per plant, because any more would mean the flowers would be smaller, resulting in smaller sunflower seeds and, in the end, a much smaller harvest per acre.

By the second month, nearly all the flowers had blossomed. My sunflowers’ smiles seemed as big as the sun itself. Watching them smile put a smile on my face. I had forgotten the last time I smiled looking at my harvest.

The yellow petals of the sunflower catch the eyes of visitors, but for farmers like Ashim, it’s the black circle in the middle that makes them smile. The bigger the circle, the higher the yield of sunflower oil. © BRAC 2023

I am expecting to harvest nearly 500 kilograms of sunflower seeds per acre this season. If I compare this to the amount of mung beans I would have normally produced in the same area over the same period, I might make up to five times as much at the market. I also won’t have to buy expensive vegetable oil from the market for the rest of the year. The stalks can be used as firewood in the kitchen, and the husks can be fed to cattle. What more could I expect from a crop?

Becoming a water engineer

As much as I love my land, the constant heartbreak of failed crops has worn me down over the past few years. Watching my new sunflowers smile now has rekindled a new, long-cherished plan of mine.

I have always wanted to engineer a cheaper way of irrigating our crops. This season, I realised the solution was always right before my eyes. We have a two-kilometre long canal that zigzags through our fields and drains into the sea. Years of no maintenance has filled the canal with silt from the fields. If we could dig up the canal again and dam it up, we will be able to hold enough rainwater to irrigate our crops in the dry season, for a very low cost.

The farmers around me are now interested in this plan, so, alongside the expansion of my new sunflower crops, this will be my next goal. If you had asked me last season, I would never have said any of this was possible.

A farmer that is adapting to – and perhaps even learning to manage – the dreaded fire dust.

Over half of Bangladesh’s population is employed in the agriculture sector. But the climate crisis is now threatening all that. 30% of cultivable land along Bangladesh’s coast – an area the size of Lebanon – is now affected by salinity. This is threatening to severely impact food security, in a country with 170 million people to feed. Nearly 10 million people in Bangladesh are at risk of going hungry because of climate impacts by 2030.

A climate adaptation clinic that supports 3,500 farmers for one year with climate adaptive agricultural inputs costs $126,000 to run. Developing countries are getting 3% of the funding they need, and 6% of projects are locally-led.

Bangladesh is an example that climate adaptation can work, but it needs to be better financed and better implemented. Three principles are crucial – that adaptation is a nexus of development-humanitarian-climate programming, that special attention is given to the most vulnerable communities and that adaptation is locally-led.

Ashim Shikari is a farmer from Patuakhali in Bangladesh. His story is told by Ayan Soofi, a Communications Specialist at BRAC.

Learn more about The Good Feed.

Contact us at thegoodfeed@brac.net.

© 2024 BRAC