Honouring 43 years of fighting poverty in Bangladesh

Reading Time: 3 minutes

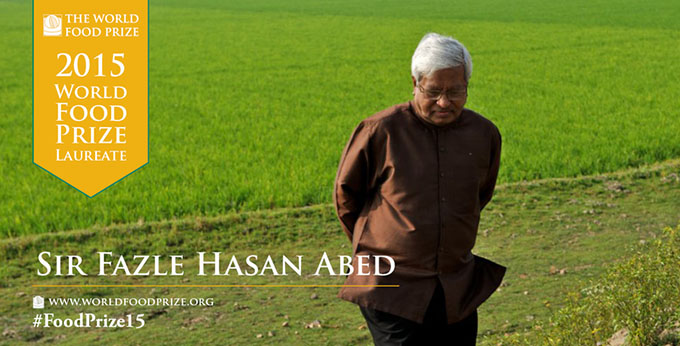

One of the high points of my career was the five years I spent in Bangladesh in the early 1990’s as the Ford Foundation’s country representative, watching the emergence of BRAC as one of the world’s largest and most innovative non-profit organisations. Today, however, I am delighted to join many others who have come to know this organisation, in celebrating BRAC and Fazle Abed, its founder, as the 2015 awardee of the prestigious World Food Prize.

This blog was originally posted on Oxfam America’s First Person Blog

One of the high points of my career was the five years I spent in Bangladesh in the early 1990’s as the Ford Foundation’s country representative, watching the emergence of BRAC as one of the world’s largest and most innovative non-profit organisations. Today, however, I am delighted to join many others who have come to know this organisation, in celebrating BRAC and Fazle Abed, its founder, as the 2015 awardee of the prestigious World Food Prize.

Born in the aftermath of the horrific Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, when millions of Bengalis were slaughtered or forced into exile, BRAC (initially known as the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee) began as a modest effort of Fazle Abed, a young Bengali who left his job as an executive with Shell Oil in Chittagong and chose to serve his people at a time of tremendous suffering. These were dire times. The new nation was devastated by the war. Its economy was in shambles. Millions of refugees were returning from India. Three years of horrific famine ensued. BRAC emerged as a humanitarian response to this crisis.

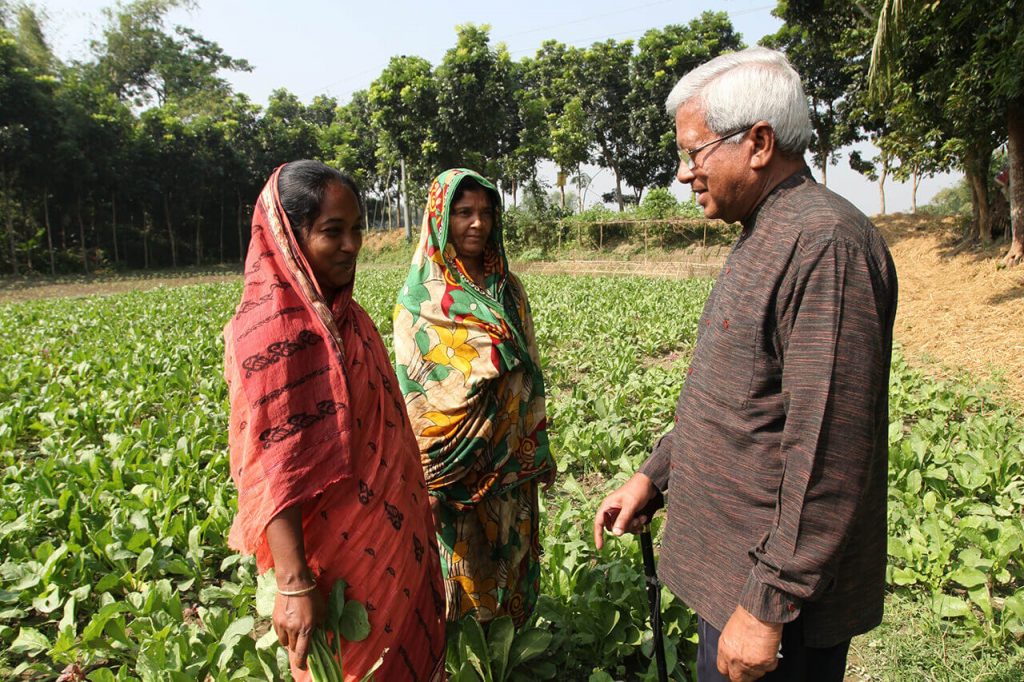

As the times years of famine passed, BRAC took on a wider mission of addressing poverty. Fazle Abed brought his business training to exploring ways that BRAC might empower the poor, particularly women, to manage their own lives. Over the years, BRAC developed and experimented with diverse livelihood programmes, from cash for work to microcredit lending, from silk rearing to fisheries, from crop diversification to dairying and many more.

Abed had a unique ability to see economic opportunity in a resource-constrained environment where no one else could and turn it into a highly successful program accessible to the poorest families. He was not afraid to take risks. He encouraged his staff to live among the people they served and to learn from trial and error. Most importantly, he knew how to develop a business plan, find investors and take a modest idea to scale.

BRAC took a modest craft initiative and created a national network of high-end crafts retail stores and a crafts export business. It took an idea for how one could purchase milk from women with only one cow and turn it into a profitable national yogurt production enterprise providing income to thousands of small local producers. Over time, such successes enabled the organisation to lessen its dependence on donor funds and support its programmes with home-grown income.

Working with UNICEF and major centres of global health, BRAC developed a highly sophisticated outreach programme in basic health services and maternal child healthcare to the rural poor. BRAC also developed a unique village-based model of primary education that brings together some 30 children in a one room schoolhouse. They recruit and train educated local woman teachers, who then offer free primary education in reading, math and social studies. This programme has been so successful that BRAC now runs some 38,000 schools across Bangladesh. And in recent years, taking advantage of reforms in Bangladesh laws governing higher education, BRAC started an undergraduate university and now offers a graduate degree programme in public health to dramatically increase the numbers of high quality public health workers.

After so much success at home, Abed wondered if he could take the lessons of BRAC abroad. With support from Oxfam and other funders, BRAC started by setting up a microcredit programmes in Afghanistan after the war, in Sri Lanka after the tsunami, in Haiti after the earthquake and in a half dozen African nations. While BRAC’s programmes were created in the unique context of Bangladesh, BRAC has been sufficiently innovative to test and adapt them to very different social, economic and political contexts across the globe.

Knighted by the Queen, Sir Fazle is known to his friends and staff as Abed Bhai, which in Bengali is a term that conveys intimacy, warmth, friendship, and respect. Abed Bhai is a soft spoken, accessible and modest man who has given his life to building an amazing organisation to serve the poor of his nation. I am proud to have worked with him both as an individual and through Oxfam. His is an extraordinary legacy and a testament to how the vision of a single person can change the world.

Raymond C Offenheiser is the president of Oxfam America. Offenheiser, who has worked his entire career in the non-profit sector, is a recognised leader on issues such as poverty alleviation, human rights, foreign assistance, and international development.