Reading Time: 4 minutes

Limia Dewan, senior manager of BRAC Education Programme’s (BEP) children with special needs (CSN) unit, met Belal after conducting a door-to-door survey in Korail slum where he lives. With more than 40,000 inhabitants, Korail is Dhaka city’s largest slum. “Out of that many people, there had to be children with specials needs who needed our attention,” said Limia. “So we set out to find them by asking residents if they knew of any specific cases.”

Meet Belal, a seven-year-old boy with Down syndrome.

Limia Dewan, senior manager of BRAC Education Programme’s (BEP) children with special needs (CSN) unit, met Belal after conducting a door-to-door survey in Korail slum where he lives. With more than 40,000 inhabitants, Korail is Dhaka city’s largest slum. “Out of that many people, there had to be children with specials needs who needed our attention,” said Limia. “So we set out to find them by asking residents if they knew of any specific cases.”

Many were able to identify these children, but used the word pagol, which means ‘mad’ in Bengali. “I felt really bad that they were being described as crazy,” Limia recounted. “People don’t understand that they actually have a disability.”

With the approval of two new laws last year, the government and NGOs have been acknowledging issues surrounding disabled people more and more. The laws include protection of disabled individuals from discrimination and more assistance for those with intellectual disabilities.

BEP set up its CSN unit in 2003, aiming to integrate children with special needs into BRAC schools and ensuring their gradual participation in mainstream education and society. In 2013, the unit established its first neuro developmental disability centres, opening one in Pabna and another in Korail, where Belal is now a student. Each centre has about 20 students along with one teacher and one caretaker. Besides learning to do things like read and write, the children are taught about ethics and manners. They play sports and are given meals, which is also an important aspect of the rehabilitation process. “Even teaching the children to not make a mess when they eat is crucial for their social integration,” explained Limia. “Most of them have made vast improvements since their first day at the centre.”

The objective of the centre is to uncover each child’s deficiency and eventually integrate them into mainstream schools. “This is their right,” said Limia. “This is inclusive education.” In addition to mainstreaming, Limia says their goal is to show that intellectual disabilities are not an expensive venture for development programmes. According to a Department of Primary Education report, three per cent of children with disabilities are considered to be severe cases, but can be in a learning environment with other children without special teachers. However, only two per cent require special attention and specific learning environments. Limia believes that this cohort can easily be reached using low cost methods in order to ensure inclusive education for everyone – not just girls and children from ethnic backgrounds. “We have to change the mindset that educating these children and mainstreaming them is costly,” she said. “It really doesn’t have to be.”

At Belal’s school, where there are seven boys and 13 girls, the little boy has proven to be a leader, like when asked to head the morning’s exercise session. “Belal is different,” explained Limia. “When we first met I asked whether he knew what school was and he said yes, so I asked him if he had ever seen a BRAC school.” Belal nodded yes with great enthusiasm and told Limia he knew where it was. Excitedly, Belal took Limia to where he thought the school was, but instead took her to another NGO-run school in the slum. “I was quite pleased and taken aback by his gusto rather than disappointed,” she said. “I saw his potential immediately.”

Each child enrolled at the centre is individually examined to determine the functional status of primitive reflexes, motor skills, vision, hearing, speech, cognition and overall behaviour. They also determine the child’s mental age as opposed to their real age to provide a better understanding of how to approach their rehabilitation. A professional psychologist then evaluates each individual report. Once they have diagnosed the type of intellectual disability, the CSN unit can determine the proper course of therapy for each student.

Belal’s mental age was revealed to be three-years-old. However, he likes to be challenged and at times can be quite competitive with his peers. He has shown an aptitude for sports and takes notice if a classmate has memorised more poems than him, striving to do the same or better. Belal’s energy and eagerness to learn is what has captured Limia’s heart and in turn, she has earned Belal’s trust and confidence.

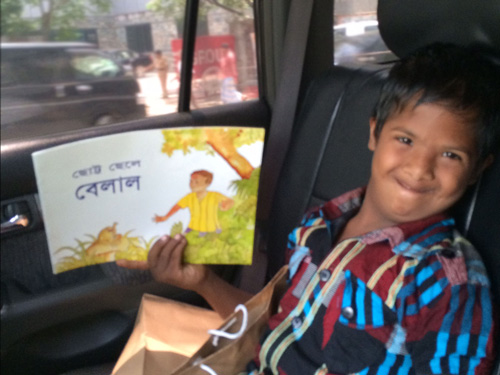

One day Belal managed to convince Limia to take him to the BRAC head office across from Korail. “I opened my car door and found him sitting in the backseat!” she exclaimed. “I was shocked yet touched, because I could tell he really trusted me.” Limia asked if he would be alright to go with her, and he said yes without any hesitation. She brought Belal to see where she works and he met some of her colleagues. “He shook everyone’s hands and sat very patiently at my desk while I did some things around the office,” she recalled.

Afterwards Limia took him to some stores nearby, as Belal had never been to any stores outside of Korail. “He was so well-behaved and I could see how happy this made him,” said Limia. “He was the happiest when I gave him a book where the main character is also a little boy named Belal.” Belal held the book and pointed at the main character on the cover. Limia remembers him saying, “This is Belal, and I am Belal also.”

Anushka Zafar is a senior communications officer and sub-editor at BRAC.