From Sulla to the world: Happy birthday, Abed bhai

Reading Time: 5 minutes

Sulla, the location of BRAC’s very first project initiated in 1972, would lay the cornerstones of what would become the world’s largest and fastest growing development organisation. Remembering Abed Bhai on his 85th birthday, we look back on BRAC’s beginning in Sulla and reflect on the many lessons to be carried forward.

One thousand hammers, eight-inch screwdrivers, shovels, handloom weaving tools, a hundred one-inch and half-inch chisels, thirty measuring tapes, pliers, saws, and a heart heavy with agony but full of conviction and indomitable hope.

Anguished, because the people in his country were in ruins from an atrocious war, but convinced that history would soon be re-written, a nation labelled a ‘basket case’ would emerge from the ashes.

With this conviction, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed and his team of dedicated volunteers made their way to Sulla on 17 January 1972 with these supplies to take part in repairing and building a nation that would become one of the fastest-growing economies in the world in a matter of decades.

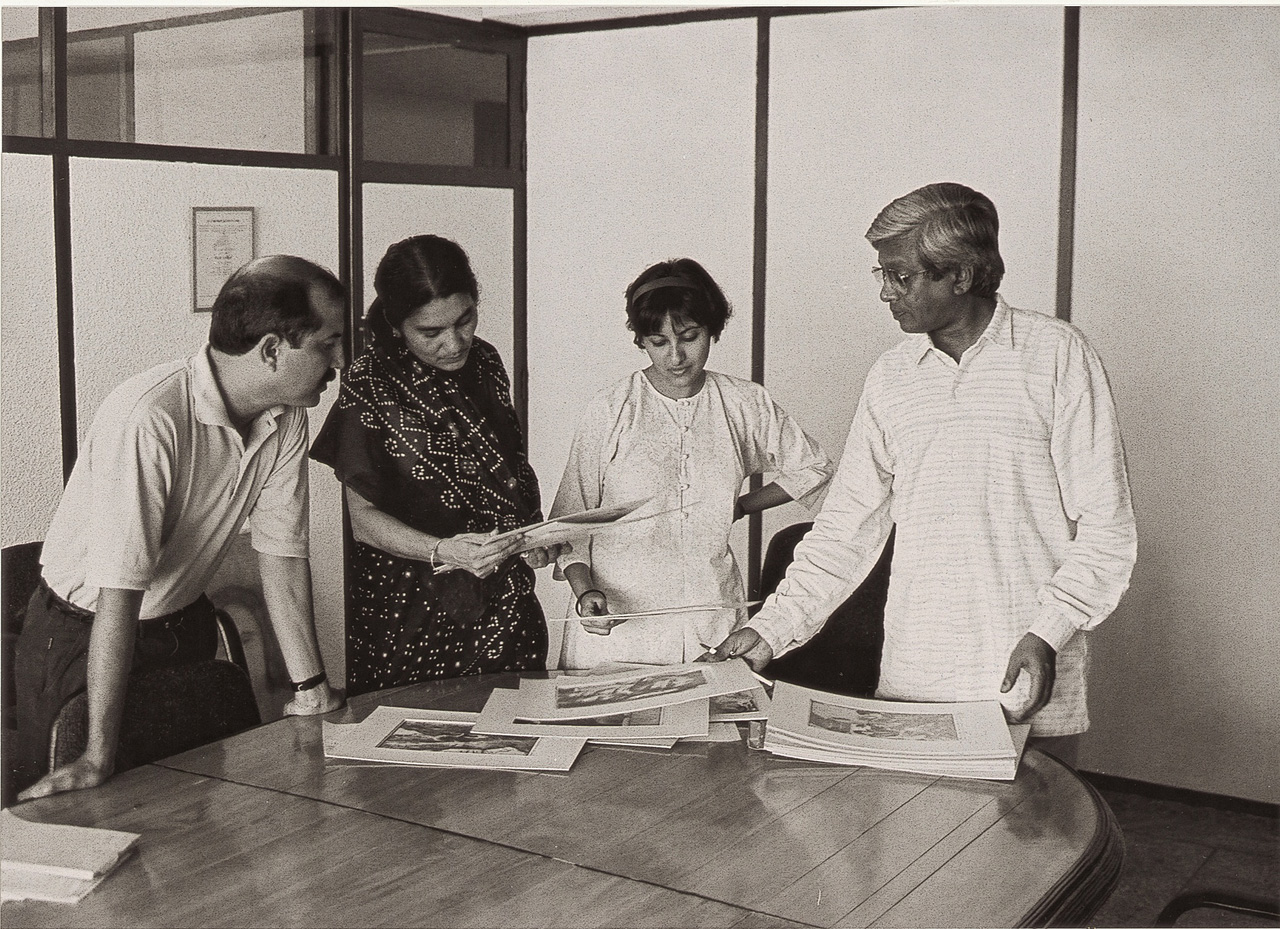

Photo ©BRAC

Understanding Sir Abed’s vision and how he created BRAC is to understand the role of volunteer movements in rebuilding the nation, the firm defiance in the face of suppression, and the dream to self-reliance. We collectively experienced the genocide and fought for our victory, and this collective experience was instrumental to building the new-found nation.

It had also brought forth conditions of possibility and a call for change. A manifestation of which may be linked to BRAC’s formation, as reflected in the Executive Director’s report for Sulla in 1972:

Rural Bangladesh with slight regional variation remains wielded to her primitive ways. But the struggle for liberation has brought about a new climate, a new awareness and desire for change. Exploitative rural leadership is being constantly challenged and a new and forward looking potential leadership awaits in the sidelines to be trained and inducted to their future roles. The people so long groping in mistrust are now receptive to new ideas and institutions which would help them to break away from centuries old subsistence economy. (BRAC, 1972: 1)

Sulla was an extremely vulnerable community. The village had an illiteracy rate of 90%, was prone to natural calamities, and faced targeted violence in the liberation war. The population of Sulla predominantly consisted of Hindu and the jele (fishermen) communities, who were subjected to extreme violence during the war. Their houses were burnt down, women were raped, and families were made to flee.

Numerous families from Sulla fled the country during the war because of the fear of persecution and returned to find their homes in ruins. BRAC’s decision to start working from Sulla, thus, reflects Sir Fazle’s intention to support the communities that are most vulnerable, not just economically but also socially.

Read more: A letter from Sir Fazle for International Women’s Day

BRAC’s selection of Sulla’s population, one of the worst-affected communities in the early years of 1970, and its continuous experimentation with how to support them reflect the early and sustaining nature of Sir Fazle’s approach—reflective, empathetic, keen on adapting based on knowledge and experience, and quick to change as and when necessary. BRAC would implement programmes, study impact while models were being implemented, and adapt to the response of the community members.

The idea behind BRAC was defined by a strong and determined vision paired with a rigorous culture of learning. No development model works in a vacuum; it needs to be tested in the context and adapted to realities on the ground. This is what Sir Fazle believed. BRAC never took even an established model for granted, rather placed at the forefront the subjective conditions of the rural community it worked with. The use of a cut-paste approach had never been in its nature.

BRAC had started with a volunteer-led rehabilitation programme but soon adopted a community-centric development model and took a more targeted approach to address the challenges faced by people who were living in the most vulnerable conditions. BRAC methodically identified and targeted the most disadvantaged groups, and not only supported them to improve economically but also enabled them to have a critical awareness of how their position in power structures prevented them from having a dignified life and how they could try to overcome the hindrances.

Sir Fazle’s BRAC was grounded, empathising with and listening to the people it intended to work with and eventually adapting the programs based on their needs.

We draw on BRAC’s decision to mobilise volunteers and understand the community’s housing needs in the early 1970s and simultaneous emphasis on securing the villagers’ buy-in before starting the construction. This sheds light on how each community intervention was done through the active participation of the people themselves. As reflected in the Sulla report:

In most cases, traditional grouping within the village had to be encouraged to work together for the common goal of Gonokendro construction in order to have the widest possible village support (…) age old feuds between groups had to be settled before construction could be undertaken in the village. As a result, Gonokendro construction was followed by an upsurge in community spirit (…) which is considered to be a precondition for any concerted action for development. (BRAC: 1974: 4)

BRAC’s measurement of success was not limited to its numbers or rates but in its ability to empower groups to such a level that BRAC presence would no longer be necessary, as mentioned in the document, “The number of cooperative societies however is by no means indicative of success to this field. The ultimate measure of success can only be the extent to which the societies are able to generate group actions to solve their problems and increase the productivity of their resources” (BRAC, 1972: 12).

Self-reliance of target groups was core to all activities and measures, even if that meant a delay in the process:

(…) quick return and immediate material benefits have been postponed (…) in favour of developing human resources to participate, guide and manage all economic and social development activities with little or no outside help. (BRAC, 1972: 2)

Sir Fazle’s single mindedness about self-reliance also helped BRAC avoid some of the major weaknesses of the predominant development models of that time. For example, BRAC was careful not to create a condition of dependence. In other words, BRAC avoided a relief-based model and instead focused on creating independent human institutions. This philosophy is reflected in the explanation why BRAC would not freely distribute seed:

Any contrary policy would lead to the damaging psychological dependence of the beneficiaries. Relief approach must not apply in the field of economic activity – credit management must be brought to the realm of everyone, work ethic must be inculcated, otherwise development would elude us. (BRAC, 1972: 16)

For the same reason, BRAC never wished to become a permanent part of the power structure in a community, rather empower the communities to negotiate their rights and secure necessary resources themselves. Thus, education and training programmes alongside self-generating cooperatives were the twin pillars of the Sulla project (Phase II) (BRAC, 1972: 1).

Read more: She was the heart and soul of BRAC

Sir Fazle Hasan Abed’s vision of empowered, independent people charted the path BRAC navigated in its formative years. For BRAC, the experience in Sulla was the foundation of the unique institutional culture and values—empathy, self-reliance, cost-effectiveness, and critical self-reflection. As we celebrate his 85th birthday, we need to critically reflect on where it all began, all that was learnt, and all that ought to be carried as we continue our effort to uplift, advance, and empower communities around the world.

This is a story of audacity of possibility that we need to craft forward, from Sulla to the world.

Sumaiya Iqbal is a Research Associate at the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development.

Historicising BRAC

What began as a humble attempt to participate in the restructuring of post-war Bangladesh, BRAC became the largest global NGO in a few decades. BRAC’s successful development programmes, deeply rooted in understanding the people and their realities, received international acclaim and the attention of researchers, other NGOs, and donors alike. Yet, BRAC’s unique approach to development, its journey and growth trajectory, its critical inflection points, and more importantly, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed’s thinking and philosophy that shaped BRAC from the beginning are little understood.

Historicising BRAC is an ambitious project that aims to meticulously document the evolution of BRAC in the context of changing socio-economic and political realities and understand and relate the role of Sir Fazle’s vision, philosophy, and leadership in its evolution. The project also aims to develop theories on BRAC’s success. Led by Dr Shahaduz Zaman, Dr Imran Matin, and Mishu Ahsan, this project aspires to contribute to the decolonisation of global development literature by telling the story of BRAC—an extraordinarily successful and innovative development organisation based in the Global South.

Cover:Sumon Yusuf©BRAC