Reading Time: 4 minutes

Life had not been kind to 12-year-old Shohag. Living in a Dhaka slum, home to some of the worst forms of poverty and depravation in Bangladesh, Shohag lacked access to basic rights such as a secure shelter, food, drinking water and an education. His father died in a construction accident a year ago and when his mother remarried, he found it difficult to see eye to eye with his stepfather. Shohag preferred to face the harsh realities of Dhaka’s streets, looking to earn money any way he could to avoid sleeping hungry at night.

Life had not been kind to 12-year-old Shohag. Living in a Dhaka slum, home to some of the worst forms of poverty and depravation in Bangladesh, Shohag lacked access to basic rights such as a secure shelter, food, drinking water and an education. His father died in a construction accident a year ago and when his mother remarried, he found it difficult to see eye to eye with his stepfather. Shohag preferred to face the harsh realities of Dhaka’s streets, looking to earn money any way he could to avoid sleeping hungry at night.

He considered himself lucky when one of his neighbours offered him a job as an assistant for a two-tonne delivery truck. The job requires Shohag to sit on top of sacks of onions on the back of the hoodless truck and ensure that nothing falls off while travelling to distant districts. When asked about the possibility of him falling off the speeding truck on the highway, he confidently replied that there is no danger; he can simply hang on to the ropes that keep the goods tied together. He added that during the winter he is given blankets to protect himself from the cold night air.

Hossain, another 12-year-old homeless child labourer in Dhaka’s river port Sadarghat, was less enthusiastic about his job. Hossain works as a porter at the launch terminal, assisting passengers with their luggage. He said that the heavy luggage, that is often too much for even an adult passenger to carry, gives him severe headaches and leg pain. Yet he does the job because he feels he has no other option. Hossain used to live with his family in a village in Comilla district. Circumstances changed when his father suddenly died from, what he called, “smoking too much”. His mother, unable to provide for him, decided to send her young son to the capital to earn his own living. Hossain learnt to be street smart and survive but when he returned to his village to visit his family, he found that his mother and two siblings had disappeared from their home. Shohag and Hossain are just two of the thousands of Dhaka’s street children.

For the past three decades, Bangladesh has struggled with the influx of migrants from rural areas to the cities. With declining employment in the agriculture sector and increasing landlessness and natural disasters, people are drawn to the glimmer of opportunities that Dhaka seemingly offers. The unskilled and uneducated migrants settle in the ever growing unauthorised slums. Hard hit by poverty and without basic livelihood provisions, they often fail to maintain shelter and care for their children. These children are then forced to fend for themselves or support their families. They are frequently subjected to some of the worst forms of exploitation and abuse from a young age. Many fall into crime, drug addiction, drug dealing, pick-pocketing and sometimes for the girls, prostitution.

BRAC’s urban street children programme (USCP), a pilot programme launched in May 2013, reaches out to these children and aims to create opportunities that were nonexistent to them before. The programme focuses on children between the ages of six and 15, living on the streets, in parks and railway, bus or launch terminals. USCP can support up to 1,700 children and operates through 17 centres located in the Mirpur and Banglabazar areas, two neighbourhoods with a high concentration of street children. The issues surrounding urban street children are multifaceted and complex; USCP tackles these problems with a comprehensive set of provisions. The centres provide free basic education and life skills development training, as well as vocational training and a secure job placement for children employed in hazardous jobs. The children are also provided with nutritious food, basic healthcare, overnight shelter, bathing, resting and locker facilities, entertainment and extracurricular activities.

In its pilot phase, the programme is learning and evolving as it progresses. Rozina Haque, programme manager of USCP, points out that initially all the children in the target age group were taught together. They were divided into two age groups – six to 10 and 11 to 15, according to their physical and mental maturity. But sometimes because of disruptive behaviour among adolescents, classes are also divided according to gender. The class schedules are customised to suit the children working during the day or night.

Haque says, “We noticed that even when the children earn as much as BDT 200 to 300 a day (USD 2.50 to 3.80), they hardly think of saving their income. When asked, they would say that there is no place for them to save money.” Because of this USCP, in collaboration with BRAC’s microfinance programme, initiated a saving scheme in late 2013. With savings, they will later be able to avail credit for starting a small business or enrolling in training. USCP aims to help 3,600 street children between 2013 and 2016.

Despite being a small intervention, USCP is promising considering the state is yet come up with a viable strategy to effectively address the multidimensional issues of the 12 million urban poor. Haque reflects, “The first two months of the programme were a nightmare; most of the children had never been schooled, they severely lacked discipline and constantly got into fights. But now the change is clearly evident; the children have become courteous, more disciplined and even helpful to fellow students and teachers.”

Haque acknowledges that some children are so deeply entangled in drug addiction and prostitution that the programme alone might not be enough to get children off the streets. She hopes that it will at least create an interest in learning for children who otherwise never thought it a possibility. She adds, “The notion that street children are unreachable because of their transient nature of living is not true. Once you get to know them and see the world through their eyes, it is indeed possible.”

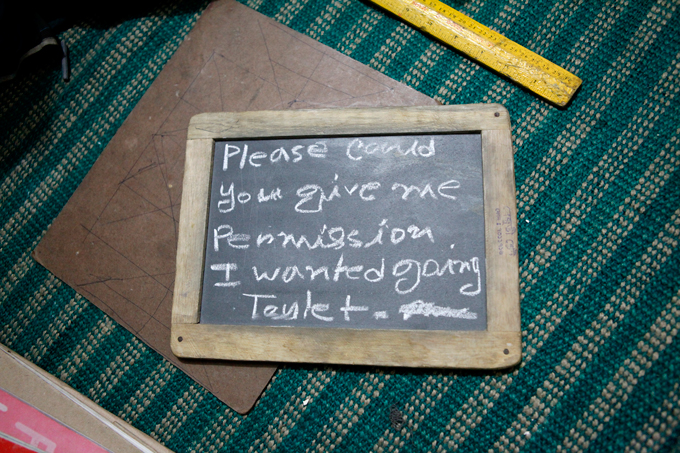

In less than a year, both Shohag and Hossain have seen a change worth pursuing. Shohag, who is a regular in the Banglabazar children’s centre, says that in the beginning he did not know how to read, write or count. But now he is able to read, write and do some basic math, even in English. He also started saving and instead of sitting on the back of a delivery truck, he hopes to own a delivery truck someday. Hossain feels more confident about his own capabilities. Unlike eight months ago, he now has basic reading, writing and math skills. He dreams of opening a tea stall with his savings, and he says he will continue looking for his family.

Where the society, community and even their parents have forgotten them, interventions such as USCP may be among the best chances these street children have in pursuing a better future. Shohag and Hossain, at least, know that they will seize it.

Asif Imran Khan is a communications officer at BRAC in Dhaka, Bangladesh.