BRAC in Uganda’s transition to a bank and what it means for customers

Reading Time: 4 minutes

BRAC in Uganda shares strategy and sustainability insights from its transition from an MFI to a bank.

Originally posted on The Center for Financial Inclusion blog.

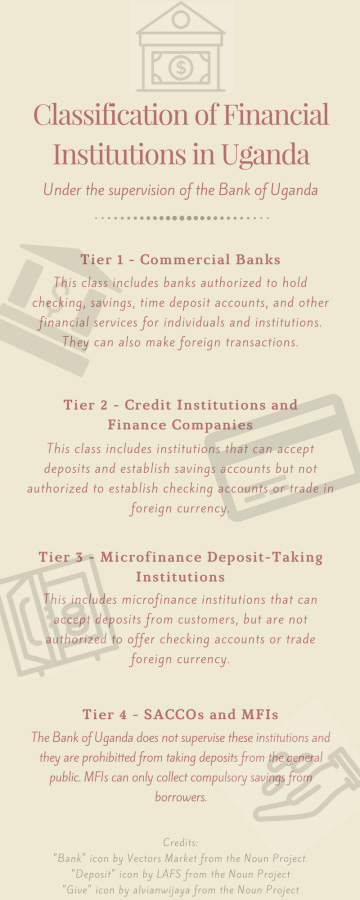

BRAC, the largest microfinance provider in Uganda, currently serves more than 200,000 predominantly rural, female clients, through more than 150 branches across nearly every district in the country. In the nine years since the microfinance company was established, BRAC has provided microloans to women (a basic loan ranges from USD 55 – 1,400), and small enterprise loans for male and female business owners (from USD 1,400 – 10,000). Its current portfolio is around USD 45 million. This year, BRAC submitted its application to transform into a bank. In Uganda, it was a Tier 4 institution, a category for unregulated credit-only NGOs, and money lenders. After the transformation, BRAC will become a regulated Credit Institution, under Tier 2, allowing it to expand its suite of services for clients – most notably, to savings accounts.

The process of transitioning to a regulated institution in Uganda is a lengthy one, and requires the organisation to strategically analyse its goals and pro-poor model. Much can be learned from this process that can inform others considering a similar transformation to expand services for clients. As with any significant change, the organisation is already facing new challenges that must be carefully and creatively navigated so as not to alienate its customer base.

Pursuing mission-aligned regulation

BRAC had been considering this transformation since 2012, but waited several years to initiate the process. “We wanted to wait until we were certain that the balance sheet was big enough, and the company profitable enough to absorb the added compliance costs of being a deposit taking entity without risking mission drift,” said Shameran Abed, BRAC’s director of microfinance and targeting the ultra poor programmes. By 2015, BRAC leadership were confident that they could begin.

The decision to pursue Tier 2 Credit Institution status, as opposed to other tiers, was also strongly driven by its social mission of promoting financial inclusion for Uganda’s poor. After some analysis, ‘Tier 1’ and ‘Tier 3’ status posed several risks that could compromise BRAC’s pro-poor mission.

The initial thought was to transition to a Tier 3 Microfinance Deposit Taking Institution, but this entailed several drawbacks. With Tier 3 institutions, despite lower regulatory costs, the regulations restriction the largest shareholder to a maximum 30% ownership stake. BRAC leadership wanted to avoid a situation where other shareholders might come in and steer the company in a different direction. As a Tier 2 institution, BRAC can hold a 49% share and ensure that the bank sticks to its mission by partnering with like-minded stakeholders.

Problems also surfaced with Tier 1 Credit Institution status, which is suited to commercial banking and invites significant added regulation. In addition to other challenges, it would mean competing with traditional formal banking institutions, instead of serving the poor. “Tier 1 regulation was really high-end,” said Emmanuel Emaasit, Chief Operating Officer of BRAC Uganda Microfinance, “we would be treading a thin-line against mission drift under commercial banking. Our clients are poor, so we thought we can still serve them best in Tier 2.”

By staying true to its existing client base under Tier 2, BRAC can focus squarely on providing services that meet their specific needs eg, by exploring savings products and money transfer services. Finally, Tier 2 enables BRAC to call itself a ‘bank,’ which instills trust and legitimacy that will give clients confidence to save with the institution.

Cross-subsidising products for people living in poverty

For customers interested in starting a savings account with the new institution, the opening balance is just USD 1.50. Because of its low-income client base, BRAC anticipates the majority of its savings accounts will be relatively small.

As a credit-only NGO in Uganda, disbursing and collecting small loans from clients only required BRAC to have loan capital on hand. But transitioning to a regulated institution that collects savings will require the bank to meet a minimum standard for its deposit base. “Small savers will not give us a large enough deposit base,” said BRAC Uganda Microfinance CEO, Jimmy Adiga. “So we opened a branch [in Uganda’s capital] to attract corporate clients who would have larger savings accounts.”

According to Adiga, these corporate savings accounts will have attractive interest and the lending function of the bank will only be for BRAC’s usual low-income client base. But what if these new corporate clients want to take out loans? The bank will put a loan ceiling in place to ensure that BRAC doesn’t drift from its mission of predominantly serving poor clients.

Ushering digital financial services into rural areas

Walking around Kampala, it would be hard to miss the pink “Mobile Money” signs at nearly every convenience store along the roadside. Mobile money is relatively new to Uganda, but about half of the country is using it. With neighbouring Kenya seeing massive success of its M-PESA platform, Adiga explains that clients are primed for digital financial services. “For the poor, it creates convenience and access,” he said, “but it’s not affordable if we run on the existing platform.”

With this transition, BRAC in Uganda plans to begin introducing mobile money to the rural poor in the next two or three years. Its goal again aligns closely with the mission of the international BRAC organisation — to expand financial inclusion and empower people living in poverty. A research report in Science looked at the impact of mobile money over six years and found that access to M-PESA enabled 2% of Kenyans to move out of poverty, with results particularly pronounced for women.

Square peg in a round hole

Early challenges are beginning to surface. Many Tier 2 regulations were not designed with BRAC’s client base in mind. For example, using a signature to verify client identity is standard practice for other Tier 2 banks. But for BRAC clients, many of whom are illiterate, signatures are often inconsistent and unreliable. BRAC plans to explore biometric identification instead.

Furthermore, rules required by the central bank to increase accountability among borrowers make loans prohibitively expensive for BRAC’s low-income clients. Every borrower from a regulated institution is expected to register with the Credit Reference Bureau. This incurs an additional cost to customers, which, for BRAC’s clients, would challenge its value proposition. Determined not to let the transition push clients away, BRAC is exploring the possibility of cost-sharing with investors who also value high quality, accessible, financial services for people.

Pursuing a change in regulatory status can seem daunting for financial service providers that serve people in poverty – and for whom certain regulatory environments are often not suited. BRAC hopes that it can demonstrate – to regulators and other financial service providers alike – the critical role microfinance institutions can play in addressing the broad range of their financial needs.

For more on BRAC’s work in Africa, see this case study on how BRAC responded to the Ebola crisis in West Africa.

Isabel Whisson is a senior associate at BRAC USA. Emily Coppel is a communications manager at BRAC USA.