A pioneer in public health policy wins US Medical Award of Excellence

Reading Time: 7 minutes

Ronald McDonald House Charities (RMHC), a global nonprofit that creates, finds and supports programmes that directly improve the health and well-being of children and their families around the world, honoured Dr Mushtaque Chowdhury for his leadership in community-based primary healthcare, poverty alleviation programmes, education for children and women’s empowerment.

Ronald McDonald House Charities (RMHC), a global nonprofit that creates, finds and supports programmes that directly improve the health and well-being of children and their families around the world, honoured Dr Mushtaque Chowdhury for his leadership in community-based primary healthcare, poverty alleviation programmes, education for children and women’s empowerment.

“Dr Chowdhury is a pioneer in education and public health policy and his work has significantly impacted the health of children and their families,” said Sheila Musolino, president and chief executive officer, RMHC. “It is an honour to celebrate the extraordinary work done by Dr Chowdhury who has had a revolutionary impact improving childhood morbidity rate in Bangladesh by 73%.”

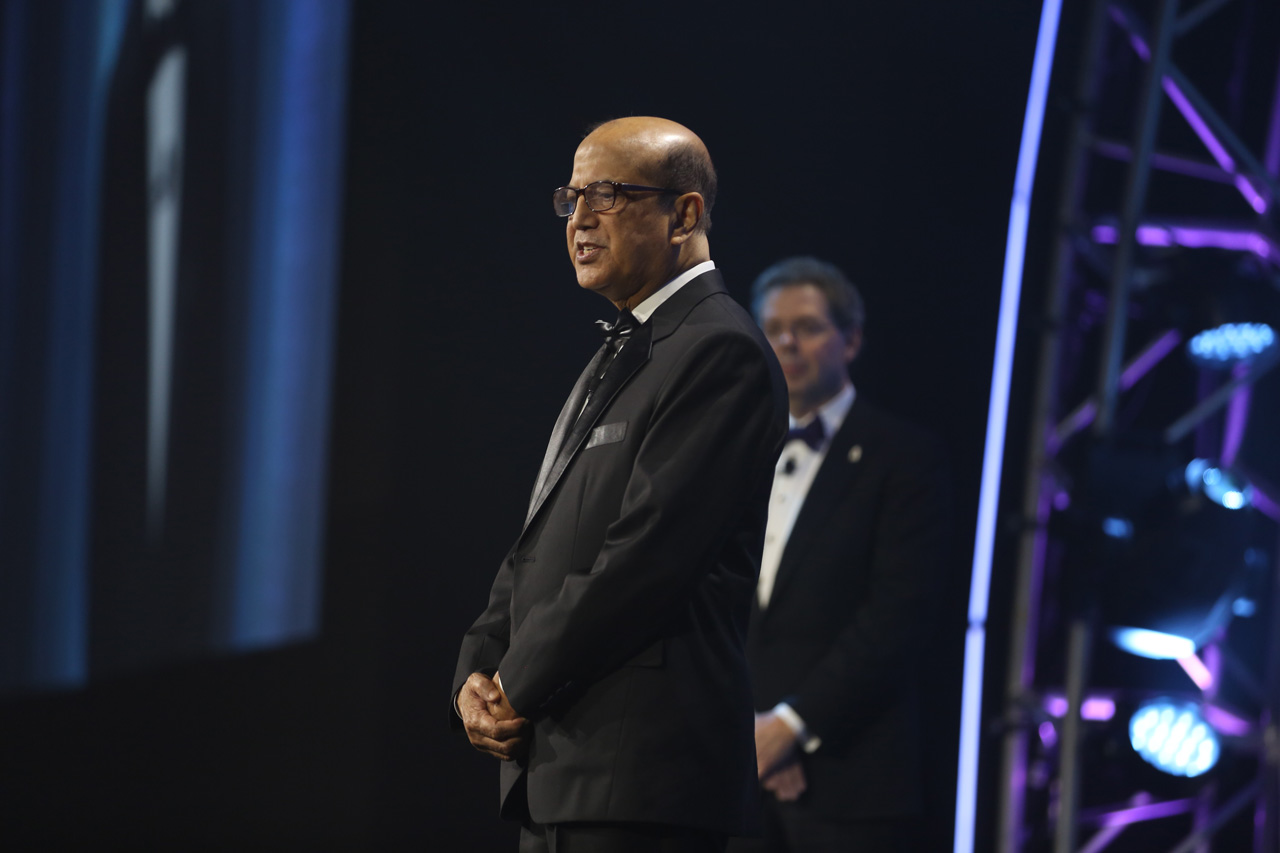

Nearly 1,200 guests came together to recognise Dr Chowdhury at the annual RMHC Awards of Excellence in Schaumburg, Illinois, where he was presented with a USD 100,000 grant and the Medical Award of Excellence.

Below is an excerpt from his recent interview, published on the ICE Business Times.

Photo: David Czuba

You have been a development professional for 40 years and have recently been awarded for your achievement. Please elaborate the details of this global recognition.

The Ronald McDonald House Charities was initiated in 1974 and as of now, it works in 64 countries serving over five million families annually. This award, initiated in 1990, was won by many eminent personalities in the past, including former US President Jimmy Carter, former US First Ladies Betty Ford and Barbara Bush, Queen Noor of Jordan, Tennis star Andrea Jaeger and Health Minister of Rwanda Agnes Binagwahu. I am probably the first South Asian recipient of this prestigious award, and I feel proud. An award committee invites nominations from prominent people from across the world and decides on the winner from a shortlist of outstanding candidates. Recognition is the central aspect of it, but it also carries prize money of USD 100,000, which will be donated to another charity of my choice.

You’ve been a part of BRAC from its inception. Tell us how it was in the early days.

When I joined in 1977 as a statistician, BRAC had only been operating for five years with its headquarters located in a small office in Moghbazar, Dhaka. The main activities were in the field, in the remote areas of Sunamganj district. Soon after joining I was sent to the Sulla project in Sunamganj. BRAC had been carrying out community development activities in about 200 villages of the haor region since 1972. There were projects on health, family planning, nutrition, education, agriculture, and microcredit. All the projects were geared towards empowering people in poverty. As the haor population did not grow or consume many vegetables, one of the projects promoted its cultivation and use. My first assignment was to evaluate the outcome of BRAC’s vegetable promotion in the villages. I spent a week in different communities trying to understand what the project was all about and how the villagers accepted it. I developed a simple questionnaire and tested it as a pilot. I was a fresh graduate from Dhaka University, and my knowledge or experience of how to design such an evaluation was rudimentary at best. Ultimately the idea of evaluating this programme was abandoned as there was no baseline to compare with. However, this failed exercise taught me the value of experimental design and non-quantitative ethnographic methods in research.

More importantly, this first trip to Sulla gave me an immense opportunity to learn about the problems that people, especially women faced in rural Bangladesh, particularly in the isolated haor areas, and see how BRAC was trying to address them through innovative means.

The villages where BRAC was working had very low literacy rate- less than 20%. BRAC designed an innovative adult literacy programme called functional education. Following Paulo Freire, the Brazilian educator-philosopher, a significant part of the technical education programme was to make people conscious of themselves and their role in society. I was deeply moved and pleasantly surprised by seeing how BRAC was making women aware and empowered. I attended several village meetings in which I found the women very vocal and articulate in explaining how they were being exploited in the family and the society. I was convinced that BRAC was doing fundamental transformational work in changing those rural communities. Such Freirean work that we did in the 1970s and 1980s laid the foundation for BRAC’s work in the years to come. The transformation we see now in the lives of women in Bangladesh has had much to do with what other NGOs and we did during that time.

Tell us the story behind BRAC’s success.

The recipe behind BRAC’s success has always been its robust, dedicated and uninterrupted leadership. Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, whom we fondly call Abed bhai, with his vision of an exploitation-free Bangladesh, has always been at the helm. I knew I would have the opportunity to learn and utilise my knowledge here directly.

Many observers have attributed BRAC’s success to its exceptionally efficient management system. The internal audit department, for example, employs nearly 300 staff. BRAC is large with almost 100,000 staff, but the management is sufficiently decentralised with a clear information sharing system in place between the field and headquarters. Observers have also pointed out BRAC’s continued and unfailing emphasis on women. Most of the programme participants, be it in microfinance, education or health, are all women. BRAC believes in scale. If a solution is effective at a small scale, we feel it is an imperative to bring it to as many people as possible. ‘Small is beautiful but large is necessary,’ as the saying goes in BRAC! The programmes are large and now reach about 120 million people, most of who are in Bangladesh.

BRAC works closely with the government but doesn’t shy away from challenging any government action that BRAC thinks goes against the interest of the people in poverty. BRAC also works in close partnership with the development partners. Some of the donors have continued supporting it since its inception. The other distinguishing feature of BRAC is its insistence on sustainability. BRAC has been establishing enterprises since the 1970s. The enterprises support its development programmes and generate a surplus for use in other development activities. 80% of the USD1 billion annual budget is generated internally. BRAC is often its fiercest critiques. The investment in research and evaluation has made BRAC one of the very few evidence-based NGOs globally. And last but not the least is BRAC’s continued commitment to its purpose. It has remained true to its goals but has changed course and strategies based on the changing needs of the people and the national and global realities.

What is the reason behind the success of NGOs in Bangladesh?

The War of Liberation has brought a massive change in the mindset of the people of Bangladesh. Most of the large NGOs such as BRAC and Gonoshasthaya Kendra are the direct fruits of the war. NGOs made good use of the changed mindsets. The prestigious medical journal Lancet has recently published a full series of articles on Bangladesh’s progress. Interestingly, one of the reasons attributed to this success is the Liberation War. The work of NGOs and, of course, the government has led to the family planning revolution in the country. This social reform brought by the liberation war was hastened by NGOs whereas such improvements are not visible in Pakistan or India. In case of sanitation, on another example, Bangladesh has done tremendously well. The rate of open defecation in Bangladesh is 1% compared to India’s 50%. Bangladesh has worked in a similar direction from the 1970s and created a base, which is still contributing to issues such as family planning, sanitation, and microcredit. The NGOs are still working to empower and make people conscious, and I believe this has contributed significantly to their success in the country over time.

What social impacts do the “ultra poor” and “adolescent girls club” projects run by BRAC have on the society?

BRAC’s programme on ultra poor focuses on the bottom 10 to 15% of the population in the poverty scale. Initiated in 2001, this programme offers a package of interventions including participatory identification of the ultra poor families, transfer of assets such as cows, goats, chickens or small grocery shops, training on how to take care of the assets, and coaching. We also give them a stipend so that they can concentrate in rearing the assets, as well as health services. Till date, we have been able to reach around 1.7 million families. Results show that 95% of the participants are able to graduate out of ultra poverty within two years and gain access to microfinance and other market-based poverty reduction tools. In 2004, the Ford Foundation and the World Bank replicated the model in 10 countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America, which produced similar positive results as Bangladesh. At present, this model is being implemented in 40 other nations of the world. This is an example of how a model developed by BRAC in Bangladesh is being used to reach the Sustainable Development Goals globally.

BRAC’s adolescent girls club model has also been replicated in many countries where BRAC works. In Uganda, for example, thousands of Ugandan girls are participating in over 1,200 such clubs. Research done by the London School of Economics found that participation in adolescent clubs result in higher use of family planning and in lowering fertility rate. This is quite significant in a society where the large family (with 6+ children) is a norm. A vast social change is being ushered in the process.

What measures have you taken concerning the health sector?

Bangladesh has done reasonably well in recent years in improving the health status of its population. This has been possible because of selected public health programmes are undertaken by the government and NGOs. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) programme done by BRAC is a good example. Other successful programmes include immunisation, tuberculosis and family planning. However, there are other issues in the health sector that need to be addressed to reach the SDGs. These include non-communicable diseases such as cancer, hypertension, and diabetics, etc. which is responsible for 65% of deaths nowadays. To address such issues we need to have a good health system and definite and sustained steps towards ensuring universal health coverage. We currently work in areas including maternal, newborn and child health, TB, nutrition, primary healthcare, eye care, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), malaria, etc.

BRAC has made significant contribution in the country’s educational sector. What new things are your organisation planning to bring forward in this regard?

The literacy rate in Bangladesh has gone up over the years, but effective literacy is still not more than 50%. BRAC is doing its part to bring children to schools. Fortunately, almost all children are enrolled in primary schools, but unfortunately many drop out before passing the primary level. The quality of education remains another major issue. BRAC is experimenting new ways of financing primary and secondary education. We are also in the forefront of using modern technology in classrooms, and we are working closely with the government. We are also experimenting new models of delivering early childhood development from birth to age 5. BRAC University has already become a major destination for the new generation. It has been ranked the top university in the private sector. The University’s School of Public Health is attracting students from over 25 countries.

What is the future of the Bangladeshi economy?

Like most Bangladeshis, I am very optimistic about the future of Bangladesh. The poverty situation has improved significantly – the proportion of people living in poverty has declined from about 60% in the 1980s to less than a quarter now. This, however, means that 40 million of our citizens still face poverty by any standard! This is unacceptable. The recent HIES released by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics shows some alarming trend. The gap between the rich and poor is growing very fast. In 2010, the poorest 5% of the population had 0.78% of the national income, which has now reduced to 0.23%. On the other hand, the share of the wealthiest 5% population has increased from 24.6% to 27.9%. There is no alternative to shared growth.