Reading Time: 6 minutes

Khichuri is a popular all-day meal in most Bangladeshi homes. What does the cost of a plate of khichuri tell us about the changes in the affordability of food? Learn about the Khichuri Index, and how the pandemic is affecting Bangladesh’s economy.

Economic figures often make sense to economists and not many others. To figure out how changes in Bangladesh’s economy are affecting different groups of people across the country during the pandemic, BRAC has begun constructing an index similar to the Financial Times’ ‘Breakfast Index’. The ‘Khichuri Index’ reflects the weighted average cost of a plate of khichuri — a popular all-day meal in most Bangladeshi homes, and the minimum meal that a four-member family would need to survive during the pandemic.

At BRAC, we are using the index for two purposes – to understand changes in the affordability of food (which can warn about upcoming food security concerns) and also to understand how those changes are affecting different groups (different occupations, genders and geographical locations). While Bangladesh is a small country, it is extremely diverse in terms of living conditions. In an area the size of Iowa, there are dense urban cities, hilly hard-to-reach areas, extremely dry, mostly infertile areas and vast wetlands. The economic scale is broad, and women and men are affected by economic changes very differently – not only because of gender wage gaps, but because they often eat differently within the household as a result of social norms.

Which genders, occupations, districts and types of khichuri were analysed?

This edition of the Khichuri Index includes data on female and male workers, so we can analyse the effects of the pandemic on the whole labour force. We have chosen to look into the situation of women in the agriculture and construction sectors, to capture a comprehensive scenario in the informal labour market. For the male labour force, the same sectors are used as previously; agriculture, construction and transport sectors.

The agricultural labourer gives an insight into rural areas, the rickshaw puller gives an insight into urban areas and the construction worker gives an insight into an occupation that exists in both areas. The incomes of rickshaw pullers and construction workers are directly influenced by the economic activities in a town.

Read more: The Khichuri Index: Measuring the economic stress level in Bangladesh

Dhaka and Chattogram represent large urban cities. Bogura, Kurigram and Dinajpur represent areas in the northern region with high levels of poverty. Sunamganj and Brahmanbaria represent the haor (wetland) areas, where the majority of families are entrenched in poverty. Gaibandha and Jamalpur represent the char (riverine) areas. Bandarban and Khagrachari are districts in Chattogram Hill Tracts – some of the hardest to reach areas in the country. Bhola, Patuakhali and Satkhira represent the cyclone-prone coastal areas

It should be noted that prices taken are from the respective Sadar (city) markets and hence might not adequately capture price changes in rural and remote areas, particularly those resulting from the ongoing monsoonal floods across the northern districts of Bangladesh.

Three types of khichuri are again used; khichuri with vegetables and egg, khichuri with vegetables and plain khichuri.

The vegetables are recommended in the prescribed diet given by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the eggs contain important micronutrients. All ingredients are readily available in local markets. The prices of ingredients have been taken from primary sources (BRAC District Coordinators).

Key finding 1: Wages for women improved in June and remained almost stable in July

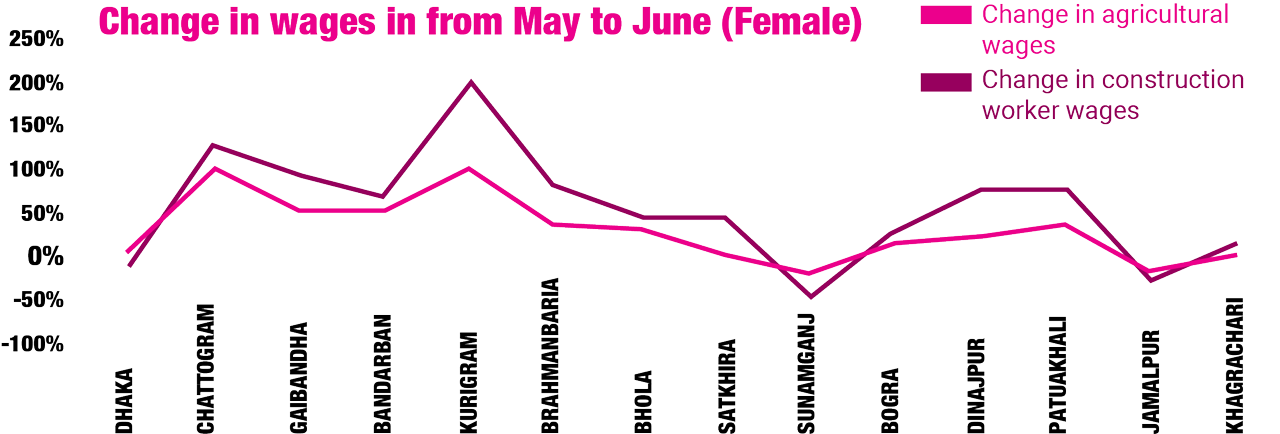

In June, wages in the construction sector rose by 18% for women and 7% for men compared to May. The increases were as a result of lockdown restrictions easing and economic activities regaining momentum. In July, improvements continued – but at a lesser rate – 2% for females and 3% for males.

It is interesting to note that wages for women in the construction sector varied less early in the lockdown (from February to March/April), compared to wages for men (6% decrease for women compared to 17% for men). The scenario was opposite in the agricultural sector, with women seeing a 7% decrease in daily wages, whereas men benefited from a 5% increase on average. The pandemic-induced restrictions could have raised the demand for male agricultural labour, especially during Boro harvesting, which resulted in higher wages for men over women in that sector.

Wages for women in the agricultural sector picked up by 20% on average in June compared to May, which increased further by 1% in July. Chattogram showed the most improvement, with 100% increase in June, while Bramhanbaria, Jamalpur and Bogura improved by 25%, 14% and 11% respectively, in July, compared to June. Wages for men declined by 13% in June, owing mostly to the 43% drop in Sunamganj, where harvesting of the main crop of Boro rice finished. Wages for women in Sunamganj also decreased by 22% in June, compared to May. The wages in Sunamganj remained unchanged in July. Agricultural wages for male labour increased by 4% in July on average, compared to June.

As cities are trying to adopt a new normal and the mobility of people on roads is improving, the daily income of rickshaw-pullers increased by 88% in June compared to May and further improved by 24% in July. While data shows that the incomes of rickshaw pullers picked up since movement restrictions were lifted, they are still yet to reach pre-pandemic (February) levels, especially in the urban areas of Dhaka and Chattogram. For Chattogram, their income is still 29% less in July than it was in February. The data for this sector was not gender-disaggregated, as women do not traditionally pull rickshaws.

Key finding 2: The cost of khichuri rose in June

The price of coarse rice hiked in June, leading to a rise in the cost of all three khichuri types. The average rise in the price of khichuri with vegetables and egg was 4%, making a meal for four people cost BDT 92.5. The rise for both the basic version and the version with only vegetables was 3%. In terms of districts, the highest rise was in Satkhira (15% for khichuri with vegetables and egg) and Bogura (11% for khichuri with vegetables and egg). The highest per plate cost was BDT 105.45 in Patuakhali, followed by Bogura (BDT 101.1). In Patuakhali, the high cost was due to high prices of vegetables and red lentils.

The cost remained almost unchanged in July, compared to June. Cost per plate did not change for khichuri with vegetables and egg, and reduced by 1% for the other two varieties. Bogura (105.9) and Patuakhali (BDT 101.70) had the highest per plate costs. Cost per plate cost rose the most in Bogura, as a result of a rise in costs of items such as green chilli, pumpkin and potato. Prices in Dhaka and Chattogram remained almost unchanged in the fourth week of July compared to June, after a slight increase in the first week of July.

Read more: Keeping the price of rice down: A prerequisite for food security

Key finding 3: The Khichuri Index for women wage earners improved significantly

Despite the rising costs of khichuri in June, women could avail more plates with eggs and vegetables with their June and July income than they were able to with their May income. The Khichuri Index for women working in the agricultural sector stands at 4.4 plates in July (almost same for June), compared to 3.8 in May. The situation is almost the same for women working in construction. While this jump is positive, affordability for women is still much lower than for men.

Men in the agricultural sector could afford 6.35 plates in May, which decreased by 12% to 5.2 in June and increased again to 5.5 in July. The index improved for construction workers in June and July, but insignificantly.

Affordability almost doubled for rickshaw-pullers, from 2.47 to 4.75 plates in July, compared to 4 plates in June. Affordability for rickshaw pullers improved by 241% in Khagrachari in June compared to May owing to a 231% increase in daily wages, and improved by a further 24% in July. Kurigram came second in June with more than 100% rise, but again fell in July owing to 29% reduction in wages. Affordability of rickshaw pullers in Bogura increased by 163% in July and now stands at 5.19, which dipped to below 2 in June.

In Dhaka and Chattogram, the affordability for a khichuri with vegetables and eggs was 5 and 4.8 respectively for rickshaw pullers and 6 and 5.3 respectively for male construction workers. For female construction workers, affordability was less in Dhaka (4.5) but equal in Chattogram (5.3). After fluctuating through March, April and May, average affordability stabilised in July. it is also worth mentioning that the khichuri index went as low as 2.3 in the last week of March from 5.4 in the first week, for the rickshaw-pullers, showing the vulnerabilities of wage earners during that time.

The economy is regaining its momentum, as evident by the trend in both wages and affordability. The drastic drop during March, April and May has mostly been neutralised in July, indicating towards some recovery.

BRAC will continue to release this index as Bangladesh tackles the pandemic, to trace the state of the economy and how it is affecting people.

Nahrin Rahman Swarna is Policy Analyst, Advocacy for Social Change, BRAC. KAM Morshed is Senior Director, Advocacy, Technology, Partnership, Migration Programme, and Social Innovation Lab, BRAC. Sarah-Jane Saltmarsh is Head, Programme and Enterprise Communications, BRAC.