An accountant with a mighty vision

Reading Time: 4 minutes

This post is the first in a series shedding light on the early years of Bangladesh, and a man whose contributions were instrumental in the remarkable strides the country has made since then. The post has been translated after it originally appeared on Prothom Alo, Bangladesh’s leading daily newspaper.

We acquired our own nation in 1971. Before that we were not familiar with the largest institution of a nation ie, the state. This left our institutions lacking in both life and lustre. Being able to establish a fabric store on Dharmatala Street in Kolkata, even during the end of the British colonial rule, was hailed as the consummate example of the Bengali entrepreneurship genius.

Independence in 1971 brought Bengalis the power to determine their own destiny and the opportunity to build new institutions. A new age of Bengali institutions began. Built around the most country’s urgent needs, they were social and cultural organisations initiated by highly patriotic individuals, imbued with a heightened spirit of patriotism.

The blighted and impoverished sight of our country in the post-independence days deeply moved its creators, urging them to build these institutions as a means to heal their grief. They dreamt of a prosperous Bangladesh, free from ignorance and poverty.

The first institution of this kind, and the first book fair of this kind

Muktadhara publishing house was born in Kolkata in the middle of the war. It was the first institution of this kind. Chittaranjan Saha, the proprietor and a highly patriotic man, had a passion to nurture the cultural and intellectual development of the newly-born nation. He ran a profitable business selling textbooks and assisted reading materials through Puthighar, his well-known house, and invested all that he earned from Puthighar into Muktadhara.

Later, Mr Saha began the fabled book fair under the banyan tree in the grounds of the Bangla Academy, which we know today as enormous Bangla Academy book fair.

The birth of the world’s largest non-profit development organisation

Around the same time, a year after the war of liberation, another torchbearer organisation called BRAC was born. Like Muktadhara, BRAC is also a fruit of the war of liberation, believing in the same dream of a country free from discrimination and poverty. The founder of the organisation, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, today stands as one of the frontrunners in the successes we have achieved as a nation.

While some got muddled in fights for power and wealth, the inconspicuous and aspiring Abed went in the opposite direction. Selling his tiny London flat and with some additional money from a friend, Vikarul Islam Chowdhury, he took himself to one of the remotest corners of Bangladesh, Sulla of Sunamganj, to support the war-ravaged local community. Two years later, in 1974, he travelled to Roumari of Rangpur to stand by people struck by famine. This was followed by expansion into Manikganj. BRAC gradually expanded throughout the country and turned into a massive organisation dedicated to supporting people living in poverty.

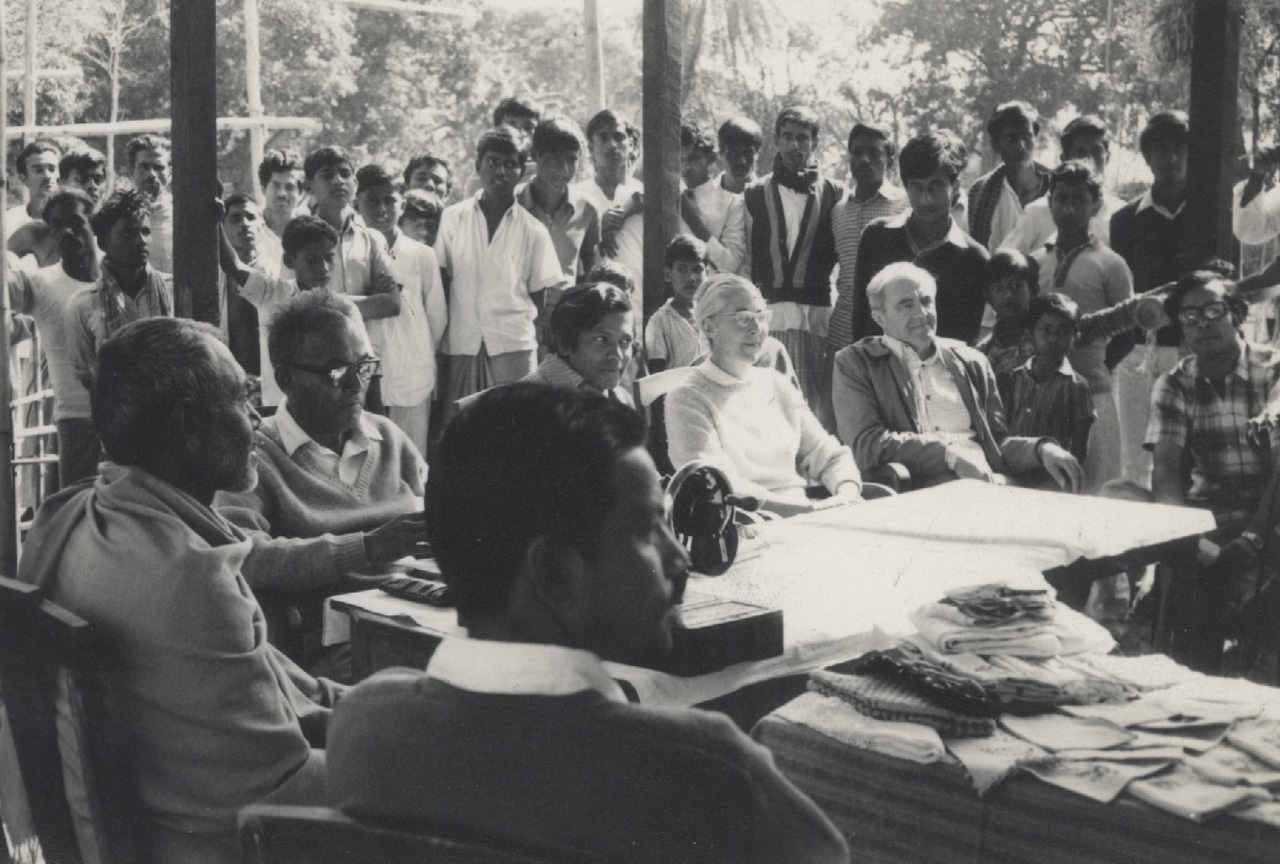

Abed (pictured seated in the middle) with visitors during the early years of BRAC.

The Japanese concept of ‘zero defect’

The journey was made possible because of a combination of Fazle Hasan Abed’s amazing organisational capacity, innate common sense and his ability to take action. I had the opportunity to visit several BRAC offices when I was working with Biswa Sahitya Kendra. I witnessed how the cogs of this formidably gigantic machine of this organisation move every day. It was a perfect metaphor for what the Japanese call ‘zero defect’. This degree of precision is indispensable in order to keep an organisation of this scale in motion.

It is built with the force and brilliance of the capitalist civilisation, and is the finest example of the highest level of attainment of that civilisation.

Yet, Fazle Hasan Abed is not the solitary king of the city of Yakshas, as eminently depicted in Rabindranath Tagore’s play Raktakarabi. Its mission is not to tear gold from the depths of the earth to build the citadel of the wealth god Kuber. Rather, its mission is guided by an ardent dream of wellbeing for mankind, a dream born out of a grieving soul, but also one filled with love.

I told Abed about my experience of seeing BRAC’s enormous activities when we met at a dinner invitation. “How did you find it?” he asked me.

I smiled and said, “It was good, except that stringency was more felt than affection.” Abed replied in his usual quiet manner, “Maybe that is also necessary.”

I agreed with what he said.

BRAC is a massive, multifaceted undertaking of the development of lives and livelihoods of people trapped in poverty, with an approach that is based on precise and calculated analysis. It is not a movement, but perhaps the unbridled fervour and grand dreams which usually accompany a movement are not fit for the momentous nature of this job.

Abed interacts with children at a BRAC school in Bangladesh.

A marriage of corporate and compassion

There are other factors that contributed to BRAC’s scale and effectiveness. Reiterating what I mentioned earlier, even though BRAC was born from social compassion, it has always been managed as a corporate entity. Every institution inherently carries the imprint of the personal experience, education, taste, philosophy and ambition of its founder. This is particularly true for BRAC and Fazle Hasan Abed. Both Abed’s education and profession are business-centric. He is a chartered accountant by profession, possessing profound knowledge on the capitalist production processes, and has full confidence in the value they hold. As a result, he knew that employing these tools would allow him to reap benefits for a greater number of people.

He did the same things to serve the greater social interest that capitalism does to serve the private interest.

He has made almost full use of the concepts of competition, target and accountability i.e, the tools of capitalism, to make BRAC’s programmes successful and effective. These methods may not have turned BRAC into a symbol of our collective dream, but they have certainly centered the organisation on a firm ground, one that is built with unparalleled capacity. For years, this mechanical, giant planet has been quietly turning on its axis to bring good to this country and its people.

Professor Abdullah Abu Sayeed, is a renowned writer, television presenter and activist.