Reading Time: 2 minutes

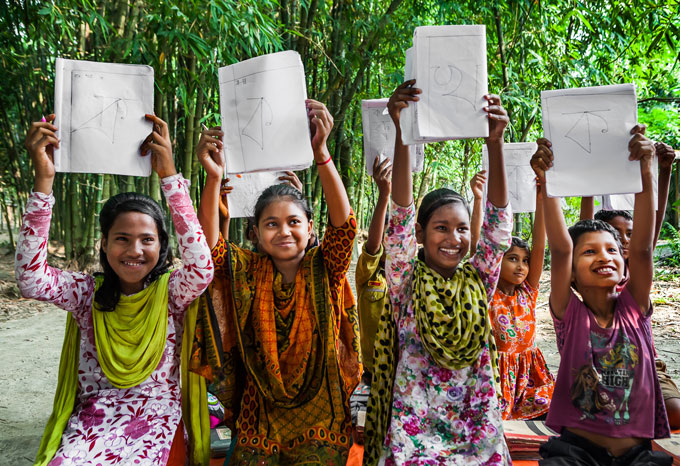

It is a weekday afternoon in Moulvibazar, Rangpur, and the melody of children chanting times tables is wafting through the trees. School is over, but students are gathered under shady trees in the village courtyards for another round of lessons.

It is a weekday afternoon in Moulvibazar, Rangpur, and the melody of children chanting times tables is wafting through the trees. School is over, but students are gathered under shady trees in the village courtyards for another round of lessons. Not just in this village, but in many others nearby as well. It is not the work of any organisation. This network of open-air classrooms is all due to the initiative of one barely literate woman.

Shamsunnahar has lived through enough adversity to know the value of education. She is the proud owner of two houses and 36 decimals of land today, but was working long, hard hours as a domestic helper just a few years ago. Growing up in an ultra poor family and married at 13, she was never given the opportunity to study. She was left with next to nothing when her husband passed away from cancer a few years into their marriage. Sending her daughter and son to school was a distant dream, but it was also a future she was willing to fight for.

Shamsunnahar with her daughter

Big changes start small, and Shamsunnahar took her first steps towards becoming an entrepreneur, getting trained on running poultry and livestock businesses. She set up her own poultry business after two years, and used the profit from her first investment to send her children to school. And it didn’t end there. She often visited their school to check their progress, and quickly understood that there was more to be done, especially for those children from poor households.

Shamsunnahar with her son

Children from poor households are twice as likely to suffer in their academic performance than those from wealthier households, according to a UNICEF report. They are also at a higher risk of dropping out from school before they reach class 5, especially girls. Apart from education, their nutrition is also at risk. Poor households often experience bouts of food insecurity, and as a result, children do not get proper nutrition and often fall sick.

Shamsunnahar identified that the students would perform better with a little help in their lessons, and the food on their plates. She rallied village authorities to organise free additional after-school support for all children, personally ensuring that children from ultra poor families attend the open-air classrooms. She soon landed a position as a member of the village school development committee, and then turned her focus on nutrition. She sought technical training on vegetable cultivation, and encouraged other households to do the same; planting quality seeds to grow carrots, tomatoes and other leafy vegetables that have high nutritional benefits and are suited to the land available to them.

“I don’t want my children, or any child, to be deprived like I was. Every child deserves to learn about the world, and be healthy and happy.”

Shamsunnahar’s initiative was not driven by big statistics. She knew from experience how children fall through the gaps because of poverty.

Refusing to bow down to adversities, she continues to promote better practices in education and agriculture, while encouraging women and the larger community to make better lives for themselves and their children.

Zaian Chowdhury is a communications consultant at BRAC.