Breaking bad – How to make good habits stick

Reading Time: 2 minutes

Recently I visited Manikganj in rural Bangladesh to see BRAC’s work in water and sanitation. A shopkeeper at a local market said that he knew handwashing was important, but soap was expensive. “What’s more expensive,” I asked, “soap or the medicines for treating diarrhea and fever?” “Medicine,” he said. He knew the answer – but that didn’t change his actions.

Recently I visited Manikganj in rural Bangladesh to see BRAC’s work in water and sanitation. A shopkeeper at a local market said that he knew handwashing was important, but soap was expensive. “What’s more expensive,” I asked, “soap or the medicines for treating diarrhea and fever?” “Medicine,” he said. He knew the answer – but that didn’t change his actions.

Experts estimate that 1 million deaths could be prevented annually if everyone washed their hands.

Why aren’t people washing their hands? Lack of access, lack of knowledge, lack of inspiration? Perhaps it is just a simple lack of habit.

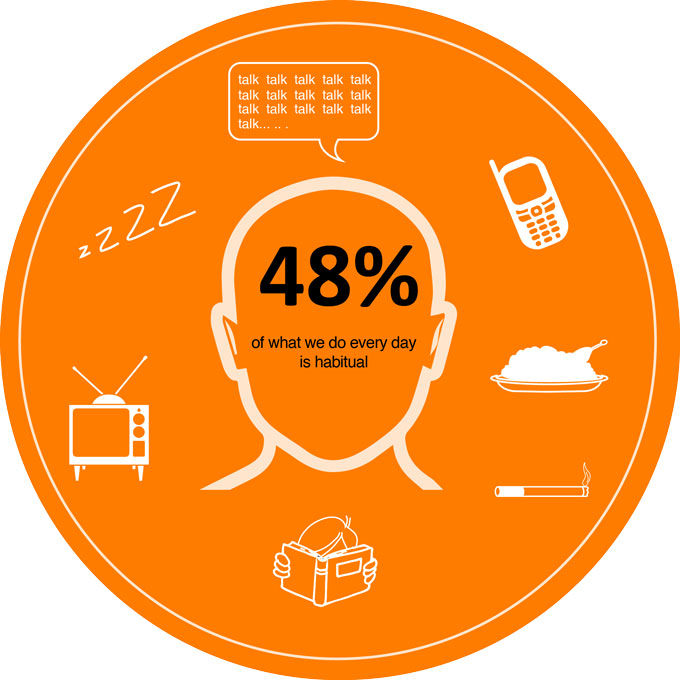

We like to think that life is a series of choices, but half of our actions everyday are the result of habits.

Habits can take anywhere from a few weeks to several months to form. The silver lining however, is that habits are self-reinforcing. Once someone builds up a new habit, it usually sticks.

Google has experimented with all sorts of strategies to keep its staff from overeating the delicious food served in their cafeteria. When ‘Googlers’ reach for a plate, they encounter a sign informing them that people with bigger plates are inclined to eat more than those with smaller plates. This simple change has actually increased the use of small plates by 50 per cent. Over time, people don’t see the sign; they simply grab the smaller plate out of habit.

Design can create habits. The invention of liquid soap, by BJ Johnson in the late 19th century, was nothing short of revolutionary for handwashing – for people who could afford it. Liquid soap is much easier to use than scattered soap pieces and so the design facilitated the creation of a new habit among its audience.

Could the same principle help rural villagers in Bangladesh start washing their hands, even if they couldn’t afford liquid soap or didn’t have a proper sink at home? At BRAC we decided to try it. We introduced a frugal solution for those who couldn’t afford to buy soap regularly: converting a used plastic water bottle into a soap dispenser. Using discarded bottles was free of charge and also encouraged recycling. Each bottle was filled with detergent powder and water.

Outcome monitoring shows that in the areas which saw water, sanitation and hygiene interventions for one year and a half, 45 per cent of participants had provisions for handwashing in or near their toilets.

Development practitioners need to get serious about understanding and adopting habit-forming interventions: Over 50 per cent of deaths globally can be traced back to bad habits. Overeating, lack of exercise, smoking, alcohol addiction and using mobile phones while driving are some of the most common.

Habits can be changed. To improve lives, we need to pinpoint key behaviours that stop people from improving their health, wellbeing or financial situations, and devise effective ways to support them in adopting new habits.

The challenge for development practitioners is to stop thinking about information and start thinking about hooks.

Shazzad Khan is a manager at BRAC’s material development unit.